Urban Legend

Growing up in East Los Angeles — specifically, the working-class Boyle Heights neighborhood that has been famously grappling with the effects of gentrification — informs the striking photography work of Gregory Bojorquez in ways both simple and complex. Bojorquez started shooting his surroundings in his teens, focusing on what he knew, from the mundane to the mournful, including families, parties, gangsters, skaters, punks, lowriders, storefronts and landscapes. The stunning, new coffee-table compilation, Eastsiders gathers much of this period of Bojorquez’s work in one place and serves as both a document to an era and a testament to the photographer’s unique place in the culture.

While other photographers were trying to capture, and some might say exploit, the essence of East LA via immersive photo sessions and set-ups for trendy magazines, Bojorquez was actually navigating the sometimes-perilous situations he was documenting. The realism and organic energy of his work set him apart and his work feels natural thanks to his relationships, his curmudgeonly charm and his sharp eye for framing compelling imagery as it was happening. Bojorquez was simply hanging out and capturing what was right there, in front of his lens. Much of the work was unplanned, instinctive and powerful.

In the late ‘90s, Bojorquez began shooting for media outlets such as LA Weekly, bringing his gritty visions and vibes to a varied mix of subjects. More work followed, including magazine and commercial shoots for the music industry. From Jane’s Addiction to Snoop Dogg to Mike Tyson, Bojorquez provided a provocative new slant on star portraiture. Rolling Stone, DUB Magazine, and more ran his work, which was fast getting recognized as important and influential.

Taken in 1998 at a Shell gas station where cruisers would stop for gas. As this photo was taken, the officer on the left spoke into his bull-horn, “You are in the line of fire.” Photo and caption by Gregory Bojorquez

Soon, it garnered attention from gallery owners. After building an impressive portfolio, Bojorquez’s fine-art photography output led to a much-buzzed-about 2007 group exhibition called “L.A. Women.” International showings of his work followed in museum exhibitions and art fairs to galleries across Europe. In 2012, Bojorquez’s “.45 Point Blank,” curated by Benedikt Taschen Jr. (the son of Taschen Books publisher), exhibited photos he took during a shooting incident at the intersection of Sunset and Vine in Hollywood. One of the photos initially made the cover of the Los Angeles Times — the first 35mm film image to do so in over a decade.

This past Summer, Taschen Jr.’s gallery in Cologne, Germany opened his solo show called “Hang Time,” highlighting images he took while socializing with friends and neighbors, most of whom represent Chicano street life and style. Subjects are often tattooed, made up and dressed down, and sometimes evoke a dark aesthetic that continues to be valued and somewhat fetishized in European countries. But Bojorquez’s nuanced work evokes more than fashion. The complexities of the city and the communities within them are presented to convey human bonds and ever-evolving environments.

A group of kids bonding at a Dennys after their high school dance in 1998, complete with french fries and cokes. Photo and caption by Gregory Bojorquez

Eastsiders, his new limited edition tome published by Little Big Man Books puts the breadth of his most potent pictures into one impressive volume. Featuring 159 images, mostly from the 1990s, it is an intimate, often stark account of East LA people and places. Representing Bojorquez’s journey not only as a photographer, but as an Angeleno who has lived a remarkable life, the book was decades in the making.

If you love unflinching, slice-of-life images that reflect urban locales and culture, this is a must have for your coffee table. To me, as a native Angeleno and Chicana who grew up in similar areas of LA around the same time, it is more than an art book. It is an experience that weaves together nostalgia, truth, pain and joy — all real and all encompassing. I hung out with Greg at his home in Boyle Heights just as the first edition was released last Spring. It sold out immediately. At his request, we held onto this interview until the second edition became available, and we spoke again. The following is a composite edit of both conversations.

LINA LECARO: I really like the relaxed vibe of this Boyle Heights backyard. Was this your family’s home? Your roots seem to run deep here. It shows in how you document your surroundings and your environment. Can you talk a little bit about that and your childhood growing up here?

GREG BOJORQUEZ: My grandfather bought this house in 1948. When he passed away, my grandmother lived here. I grew up all around the Eastside area, not just Boyle Heights. These places have been familiar to me my whole life. You have connections with friends and their neighborhoods. I got to know different people from different parts of the Eastside — from here in Boyle Heights, and also El Sereno, Montebello, Pico Rivera and Highland Park.

How did you get into photography and what did you shoot when you started?

Well, I had a friend whose dad was a photographer. He did rock and roll and blues photography, and I liked what he did. So, I just took some classes in high school and I had a lot of success. I entered photos in the State Fair and the County Fair, and I won Best in Show. I got these free classes at the Art Center and I went to [Los Angeles Community College]. For my first two small projects, I photographed things I was afraid of. So, in ‘86, I photographed homelessness and Skid Row. I’d take the 40 bus over there and it’d be like another world. And then, the other thing was fear of getting old. I spent some time in a couple of convalescent homes photographing old people. It was a trip. A lot of people these days photograph homelessness as some kind of sensationalized thing. It’s kind of like this shock gimmick thing. I was always more about humanizing people.

I was living at an apartment complex in Montebello that was across Beverly Boulevard from a couple retirement homes. As a kid, seeing the old folks with their wheel chairs and walkers hanging out in the front evoked a sort of sadness from me. I think that sadness and the fear of getting old like them is what drove me to get permission and to spend time with them. The lady this photo was kind of far gone with dementia and didn’t speak but she smiled when I took this shot. Photo and caption by Gregory Bojorquez

The publisher of Eastsiders put in a lot of the gang-type people, but a lot of the project really isn’t that. And even with those kinds of pictures, I wanted to humanize. I wanted people to connect and not look at these subjects as monsters. Because we were hanging out, you know what I mean? We were hanging out and we were having fun, and I’d just start taking pictures.

I wanted to humanize. I wanted people to connect.

Now some people know somebody who knows somebody from a gang or a neighborhood. When the photographer shows up it’s like, these people are ready for pictures. And now because of social media and Instagram, they want to look like the guys in these pictures. So, now you have all these guns and stuff that I don’t think is really necessary. It seems like some photo shoots go even further, showing lowriders, and they’ll have a girl that looks like a chola girl, but she’s not. She’s really a model and she’s pointing a gun. For some people, that’s a great photo, but to me that’s a production.

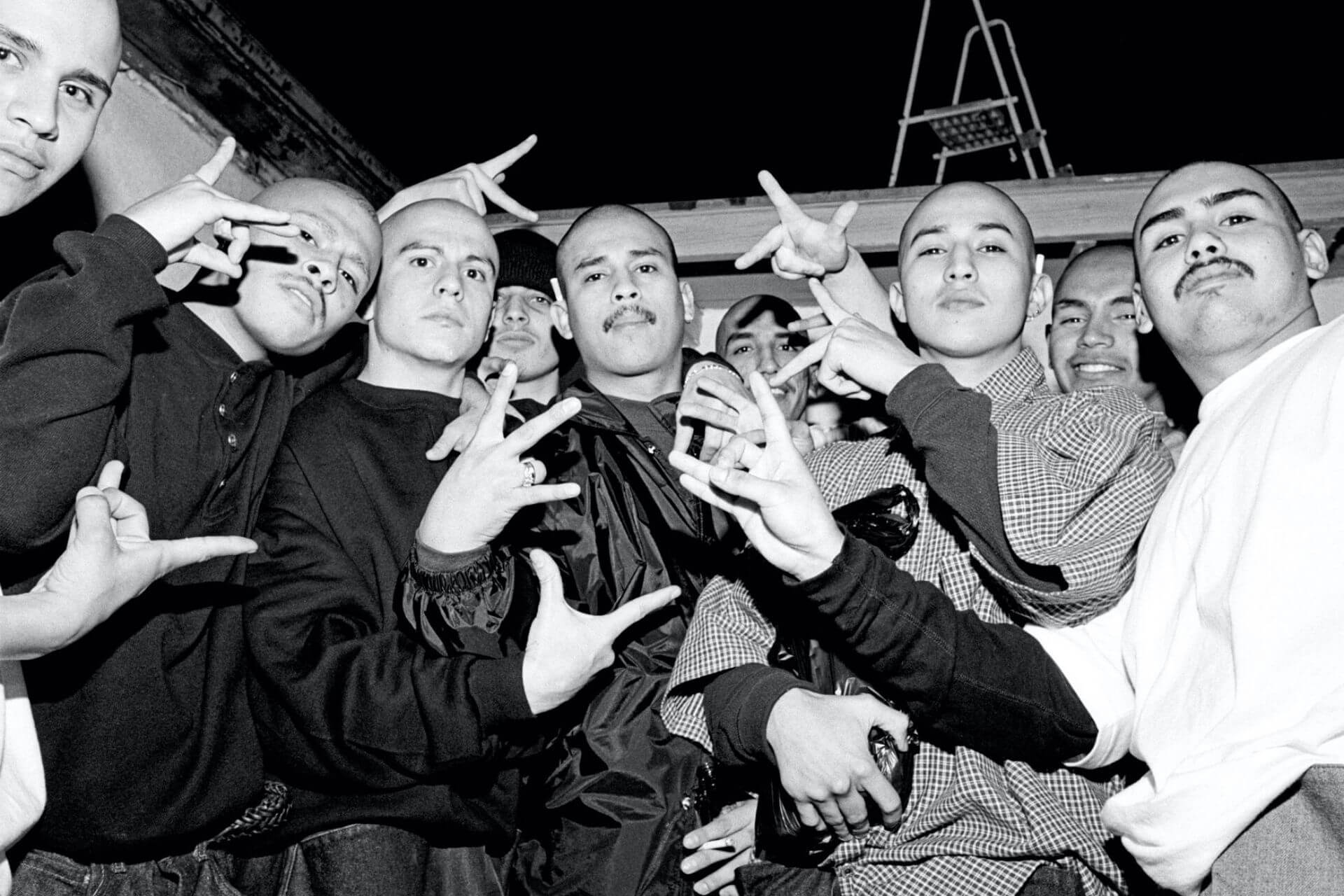

Taken at a 1997 at a backyard party. Members from three LA gangs —The Lott, East LA Trece, and King Kobras — posed together. Less than 30 minutes after the photo was taken, a teenager from The Lott was fatally shot twice by a rival on the street in front of the house. Photo and caption by Gregory Bojorquez

Do you blame social media for the lack of authenticity these days?

Instagram. Yeah. The whole interest in graffiti and gang tagging, I think it made a resurgence because of Instagram.

But authentic images invite danger, don’t they?

When I was photographing the Eastsiders project, there were times where there were drive-bys and stuff. I could have taken a photo of this guy hanging out of his car, but I thought, ‘What would that photo do?’ It would just be incriminating, and it’d make me like some kind of a snitch or something. There were people I knew who were doing things that were not legal. And I wouldn’t try to photograph them with someone else or put those people together. I didn’t want to criminalize anyone. I’ve made a living in photography since 1997. The East LA stuff and the gang-type stuff is what a lot of people know me for, but they don’t know my whole body of work — the magazines and media stuff. A lot of my pictures are syndicated through Getty now too.

Eastsiders covers a period from 1995-2000. How did you start to focus on images that would ultimately end up in the book?

When I started taking these pictures, I would tell everybody [that] this is going to be a book. I entered this contest at George’s Gallery on Vermont Avenue, which was next door to X-Large, the store owned by one of the Beastie Boys. They had an Annual Photo Derby contest and it was like a $20 entry and anybody could enter. The place was just wallpapered with prints and it was winner take all. My print “The Freaky Girls” [in the book] won. Then, the LA Weekly was doing “The Last Picture” on their back page, and they ran stuff from my Eastsiders project.

It’s funny how our paths have crossed in different ways. I worked next door to X-Large at Y-Que Trading Post on Vermont and I started writing for the Weekly around that same time. I remember you shot so many cool subjects for the Weekly back then.

I started going to a lot of music shows. The ones that I was able to actually photograph a lot were the hip hop ones because it was more underground. There weren’t many photographers doing it. It wasn’t as mainstream. There were these shows called Unity and the guys from Loud Records had, like, Wu Tang and then they brought up, like, Xzibit.

I shot lots of shows at The Hacienda in Downtown LA. It was really crazy and hot. They also did stuff at the Rodeo Inn on Washington in Pico Rivera. So I started getting hired by record companies and magazines to do stuff and then it just kind of steamrolled. I started getting a lot of work. I had my office space at the Crossroads of the World on Sunset Boulevard right by the Weekly.

(Left) I met Dan and Patrick of The Black Keys at Epitaph Records on Sunset Boulevard to shoot them for the LA Weekly music-issue cover. The photo predates their huge success that was to come. (Right) Kobe had completed the 3-peat the summer I took this photo in Beverly Hills as part of a Dub magazine cover shoot. His wife Vanessa, pregnant with their first child, was there with him along with two off duty police officers as security detail. Photos and captions by Gregory Bojorquez

What are you proud of from your time shooting for LA Weekly?

I like the [former Los Angeles Mayor] Antonio Villarigosa cover on the 6th Street Bridge, which is now renovated. I like the Queens of the Stone Age and The Distillers photos for different music issues because I guess those people ended up having a love connection down the line. [They did, but are now divorced]. The Black Keys. The Locust — that one was a nightmare. They wanted me to go to [Tijuana] as they were doing a show there. Coming back across the border on a Friday night took me like three hours at the border. I did the first Coachella for the Weekly. At the same time, I also shot a lot of car stuff for [custom car-culture magazine] Dub. That magazine really did very well for a while and I was there for six years.

When you look at your work, especially the Eastsiders stuff, do you try to step back a bit and view it from an outsider’s point of view? If so, what do you think people see and feel? Like, I see your work and so much of it is familiar to me. It reminds me of the richness of the neighborhoods I’ve lived in, but also my desire to escape the limitations of growing up in them. And since so much of the culture becomes celebrated, or as some feel “appropriated,” appreciation for a lot of it becomes complex.

It’s a moment in time. A lot of those photos are over 20 years old. So for some people that’s like a long time ago. On the personal level, people contact me and email me, ‘Oh, my brother’s in this picture.’ And I think about it and realize that it’s 25 years ago — half of my life ago. Again, it comes back to hanging out. Wherever I was, I shot. A lot of the work is from a spot on Fifth Street where I had a friend who lived nearby.

You know, when you’re hanging out, you take pictures that no one else is gonna take. Look at a guy like [legendary New York street photographer and fifth Beastie Boy] Ricky Powell in New York. [For] a lot of his stuff, he was hanging out in the Lower East Side and that’s what made his pictures cool. Boyle Heights has the highest density of Mexican-Americans in the nation, so that is a lot of what you see. I didn’t choose the images for the book. I would’ve probably picked more families and old people, and less gangsters.

Well your book editor clearly knows what will resonate with art lovers. Speaking of which, a lot of your photographs of females are pretty provocative. What’s your take on how you shoot women?

I went to a party and someone called my work sexist and I was like, ‘sexist how?’ I’m a man photographing women. My stuff doesn’t have all out nudity or sex acts or anything like that. I curated this show called “L.A. Women” and I put my friends Mr. Cartoon and Estevan in it. It was celebrating women.

I was going to ask you about Estevan Oriol. He did a book called L.A .Woman featuring mostly Latinas that seemed to be influenced by that exhibit. What do you say to people who compare you to him?

He’s a really hard worker. He’s driven. I’ve never had anything competitive with him. He’s great. If you want to compare me with something great. That’s fine.

What are you thinking about in terms of your work and subjects you might want to tackle next?

I don’t know man. Right now, I’m looking at the television and thinking I should be taking pictures in Ukraine.

Really? But that would be pretty dangerous.

Well, it’s dangerous out here.

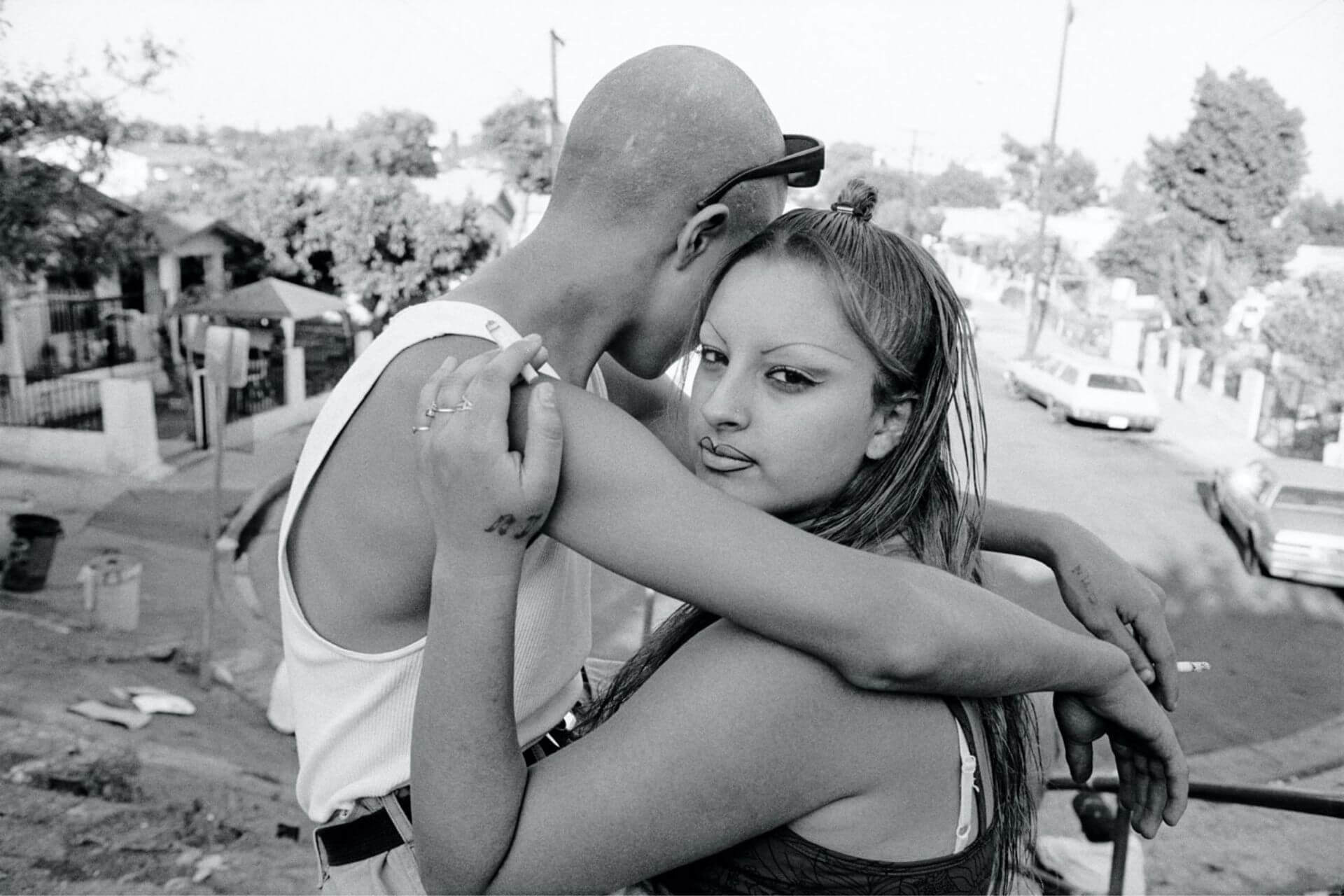

These two Little Valley gang members were making out and smoking cigarettes at the top of the stairs at the Princeton Street dead end. Photo and caption by Gregory Bojorquez

But it’s getting less so thanks to gentrification. Or is it?

Shit changes. Sometimes it’s not for the best and you know, you’re gonna lose out on some cultural things. It feels kind of sad, but for the most part, like here in Boyle Heights, people just want to get out of here. They don’t want to raise their kids in a gang neighborhood. I mean, there’s a girl who lives on the corner. She was telling my girlfriend how she wanted to go to school and do things. Now she’s pregnant by a guy in the local gang.

There’s a lot of old people that have houses over here, too, and they rent them to families. They offer the houses to the families to buy and the people just want the cheap rent. When that old person dies, their kids put the house on the market, and they sell it for the most money they can. They’re not trying to give the renters a break because they lived there for 30 years.

Well that’s why books such as Eastsiders are so valuable. They remind us how things were, for better or worse. So what do you want the takeaway to be from the book and your work in general at this point?

That it was always spontaneous. That it’s more of a whole community thing. You know, sometimes with certain edits, it looks like just a gang thing. That’s just an element. There’s a fascination with things that are tied in with crime. But, it goes a little deeper. People just appreciate it for many reasons.

What are you working on next?

I spent a lot of time in the Hollywood area. I lived there from 2001 to 2012, so I have a lot of stuff I shot working and hanging out there. I want to put out something like an answer back to Eastsiders, because people think I just photograph East LA and that’s it. I want to show a whole other thing.

Gregory Bojorquez’s photography is on display at “Deja Vu All Over Again,” a solo exhibition featuring work from Eastsiders and more at These Days Gallery, 118 Winston St, Downtown Los Angeles. Open now through October 31, 2022. www.thesedaysla.com

Eastsiders is also available at Arcana Bookstore, 8675 Washington Blvd, Culver City; in store or online www.arcanabooks.com, and via the publisher, Little Big Man Books’ website, www.littlebigmanbooks.com.

Help us sustain independent journalism...

Our team is working hard every day to bring you compelling, carefully-crafted pieces that shed light on the pressing issues of our time. We rely on caring supporters like you to help us sustain our mission. Your support ensures that we can continue to provide deeply-reported, independent, ad-free journalism without fear, favor or pandering. Support us today and make a lasting investment in the future.