Holly and Goliath

We celebrate deeply reported journalism that is dedicated explicitly to environmental, social justice and sustainability issues. Our magazine was launched during the peak of the pandemic and has been swimming against the tides of conventional wisdom ever since. We started with high ambitions to produce meaningful work that crosses boundaries, provokes discussions, inspires reflection and speaks to the times in ways that prove timeless.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This piece has been updated since it was first published to reflect new reporting, particularly about the contentious training drills at the Anacortes Fire Department. This update also includes some language changes and additional sourcing for the purpose of clarity and makes two corrections, as detailed at the bottom of the piece.

Holly vanSchaick is nobody’s idea of a union basher. As a career firefighter in Washington State, she has paid union dues for 11 years and served in union leadership or liaison positions at two different fire department locals. She believes passionately in collective bargaining and in giving workers a strong voice to protect them from mistreatment and abuse.

That, though, has not deterred her union, the International Association of Fire Fighters, from moving to expel her – not, she believes, for any violation of her membership oath, as she has been charged, but because she has been willing to call out what she sees as gross mistreatment of her fellow firefighters at the hands of union colleagues.

The case against her is vaguely worded and difficult to summarize beyond the blanket contention that she has somehow wronged her union brothers. Even the rank-and-file firefighter who put his name to the charges acknowledged to Red Canary Magazine that they were “hard to follow” and he was “pretty embarrassed that an actual reporter read them.” VanSchaick’s supporters, for their part, say the charges are bogus and the union does not know how to stand up for its women members. The IAFF would rather ostracize vanSchaick as a whistleblower, they say, than address her complaints about a toxic firehouse culture and acknowledge the union’s role in perpetuating it.

The conflict began in the small fire department where vanSchaick works, in the ferry port town of Anacortes, Washington, 80 miles north of Seattle, where a series of overlapping scandals led to months of official investigation late last year. The situation has escalated rapidly as union leaders from across Washington state line up for the fight, and activist women firefighters up and down the West Coast join vanSchaick’s closest coworkers in rallying to her side.

Since the IAFF is one of the country’s largest and most influential public-sector unions, the showdown has a David and Goliath quality to it. It also raises the crucial question of what unions owe their members, and vice versa. The IAFF’s code of ethical practices says it has a “high fiduciary duty and sacred trust” to serve its members’ interests. But a growing chorus of critics accuses IAFF leaders of treating some firefighters as more equal than others and reducing women and racial minorities, in particular, to second-class citizens subject to hostility and discrimination.

I didn’t do anything wrong. It’s all about ‘catch the snitch.’ How can we progress if that’s the mentality?

Worse, those critics say, the union frequently excuses inexcusable behavior by those it favors and goes after anyone who objects. That is what vanSchaick says is happening to her. She is not the only Anacortes firefighter to come forward about the disturbing events that have rocked the department. But, she is arguably the most effective and the most outspoken. (One of her male supervisors, in a written testimonial urging the IAFF to drop the charges against her, praised her “unwavering ability to stand up for what she knows is right.”) She is also the only one, so far, to have been singled out for punishment.

“It’s so infuriating,” vanSchaick says. “There are not even words to describe how infuriating it is. The IAFF is supposed to represent us, but its failure to support those of us who are not white men is beyond disappointing. I didn’t do anything wrong. It’s all about ‘catch the snitch.’ How can we progress if that’s the mentality?”

The IAFF says it is committed to increasing diversity in the fire service and opposes discrimination and harassment “in all forms and all types of environments” – a line echoed by the one senior union official who agreed to comment for this story. Ricky Walsh, the IAFF representative for four Northwestern states including Washington, and the organizer of a pending disciplinary proceeding against vanSchaick, acknowledged there was still work to do in a fire service where 96 percent of career employees are men and 82 percent of them are white — a far more dismal record of diversity than the military or the police.

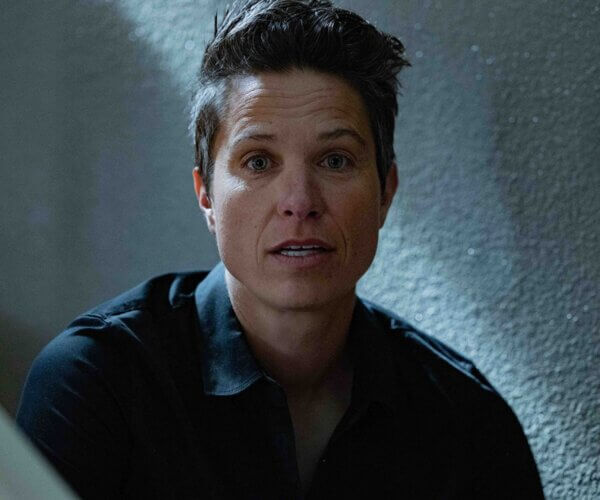

Holly vanSchaick at her rustic home where she likes to garden and tend to her goats. Photo by Scott Sullivan

Still, Walsh said he was proud of the union’s work in what he called “the transition to hiring females.” While he wouldn’t comment on the specifics of vanSchaick’s case ahead of next month’s disciplinary hearing, he insisted, “We have made significant strides to change the culture.”

The facts of vanSchaick’s case have been unusually well documented, because Anacortes’s city leadership hired Rebecca Dean, a specialist in employment law from Seattle, to conduct an independent investigation. Dean spent more than three months looking into allegations of systemic gender and age bias in the city’s 30-strong fire department and compiled her findings into an exhaustive report, obtained by Red Canary Magazine. While she ultimately found no discriminatory intent, Dean was far from generous in her assessment of the three union executive board members accused of the misconduct.

Their behavior, she wrote, raised “substantial questions about their leadership and judgment” and “undermined… the City’s commitment to a department that supports and encourages women members.” She described the union president’s behavior as “boorish” and said the other two had subjected firefighters under their command to mental stress and risk of injury.

VanSchaick, who is 44 years old, was not much involved at first. She had a reputation as a straight shooter and an advocate for women firefighters, and suspected that the executive board members were not happy when she was appointed as her shift’s Labor Management Committee representative – their point person for union business. She didn’t see the board members much outside of union meetings, though, because they worked on other shifts, meaning that they didn’t work or train with her, much less spend nights at the station eating and sleeping under the same roof while on call.

At the same time, vanSchaick retained a vivid memory of her rookie experience as the first female firefighter ever hired by the Eastern Washington city of Sunnyside, and the support she wished she’d had then from colleagues who saw her being mistreated and said nothing about it. One captain, in particular, made constant disparaging remarks about her body, told her she didn’t belong and expressed disappointment when she got through a rigorous physical test known to be challenging for men as well as women.

“I was a mom with four kids and I passed the test,” she recalled. “I should have been able to be proud of myself. Instead, a small number of men treated me as a pariah and the other guys stayed quiet. They were afraid – they didn’t want the social discomfort of standing up for me.”

Once her probationary period was over and her high marks removed any question about her competence, vanSchaick filed a complaint about the captain, including an allegation that he’d hit her and left bruises on her leg that did not fade for several days. The city conducted an investigation, but it largely fizzled after the IAFF intervened, and vanSchaick said the aggressive, sexually charged taunts from her colleagues only grew worse. At one point, vanSchaick says, a senior union official called her on her cell phone and spent several minutes chewing her out for causing trouble. “He told me, women like me are the problem, and good men like [the captain] don’t deserve to have problems in their careers,” vanSchaick recalled. She left the department shortly after.

Now, in Anacortes, she watched a similar dynamic playing out. First, the union officers put two of her colleagues through training drills so tough they felt they were being singled out for humiliation. Then, as the scandals piled up and vanSchaick felt compelled to speak out, the union came after her.

***

The trouble began because the Anacortes union officers, all of them lieutenants with command authority over the firefighter-paramedics on their shift, believed that training requirements for firefighters should be more squarely focused on physical strength – throwing heavy ladders, wielding heavy equipment, dragging bodies out of burning buildings and so on. As Red Canary Magazine reported in June (“Houses on Fire”), this is a common viewpoint in firehouses around the country, especially among large, young male firefighters in peak condition. But it also is controversial because it automatically puts older or smaller firefighters – including most women – at a disadvantage and overlooks the fact the vast majority of calls are for medical emergencies that require other, softer skills.

What made these union officers unusual was that, according to the evidence laid out by the independent investigator, they were willing to circumvent the authority of their own training chief and go beyond Anacortes department policy in the drills they ran with firefighters under their command. And, they didn’t back off even after one of the firefighters they were supervising injured his arm and went on disability leave, first for work-related mental health reasons and later for physical rehab too.

That firefighter, Tom Nelson, had been with the department for 20 years when, according to the Dean report and a number of other accounts, he was repeatedly made to perform what was already a challenging fire entry and rescue drill under conditions that, in a live fire, would fall short of safety standards stipulated by Washington state law. Nelson was not the only firefighter to be put through this drill by Qben Oliver, a former Green Beret who at the time – June 2020 – was the local union secretary as well as a lieutenant on his shift. But Nelson said he felt picked on because of his age (he was 52) and because Oliver made him keep at it even after it became clear it was too tough for him. (Oliver, by his own account, ran a two-person window rescue drill, where state law calls for at least three people on scene in a live fire and, more commonly, four.)

“It sounds like you are trying to get rid of me,” Nelson says he told Oliver. According to the Dean report, Oliver just laughed. But the drills depleted Nelson to the point where he nearly vomited, he says, and were a contributing factor to the breakdown that, soon after, caused him to spend five weeks in a residential mental health facility for work-related post-traumatic stress. (Oliver challenged Nelson’s assertion that he ran the drill for “several training sessions in a row” and denied circumventing the training division. He said he had no direct knowledge of Nelson’s mental health struggles and added, “The intent was never to humiliate him.”)

The maneuver that caused Nelson’s injury — lifting a 28-foot ladder on his own — is most commonly performed by two firefighters, not one, because a 28-footer is a monster tall enough to reach a third-story window. The training division had, at the time, agreed to conduct one-person drills with a 28-foot ladder, but according to the Dean report and a department leader who spoke with Red Canary Magazine, this was on a trial basis only. (Oliver disagreed.) While some in the department adopted a low-shoulder lift and a “flat raise” method for extending the ladder against a wall, following language on the assigned skill sheet, the drills run by Oliver and another union official, Dan Lamp, called for a more difficult high shoulder lift, not specified on the skill sheet. Many fire departments discourage this method, because smaller firefighters lack the physical leverage to perform it reliably and it can lead to injuries like Nelson’s.

It wasn’t just the physical demands that nagged at Nelson. Oliver, he said, kept telling him how great it would be if he retired. The two even discussed Nelson’s retirement finances. The independent investigator characterized these episodes as “the kinds of casual discussions and stray remarks that occur in any workplace” and accepted Oliver’s contention that Nelson initiated the conversation about finances. Nelson, though, kept worrying about his future, especially after he learned that Oliver and his two union colleagues had talked to the chief about implementing new training standards at an irregular, unposted meeting that the rest of the department did not find out about for three days. According to the chief, whose signed minutes of the meeting later circulated around the department, the union officers suggested a “cutoff” for firefighters who could not keep up. (Oliver told Red Canary Magazine the meeting has been “wildly mischaracterized.”)

The IAFF is viewed with suspicion if not outright hostility by Black and female members, who often establish their own separate advocacy groups and see the union not as a partner but as an obstacle to securing their workplace rights.

Brooke Ringe, a 14-year veteran, felt similarly picked on when she, too, was told to raise a 28-foot ladder using the high-shoulder lift and to complete the maneuver in less than a minute. According to the investigator’s report, Oliver and Lamp would make her do the drill repeatedly and pushed her to continue even after she had completed it to their satisfaction. Ringe was worried that she, too, would be injured if she kept going too long. She later wrote to city officials: “I felt like the continual drilling was aimed at making me look bad, and not to make me better at my job.”

The behavior of Oliver, Lamp and the local union president, Chris Byer, caused many firefighters to worry that the trio felt they could dictate department policy to Fire Chief David Oliveri. And, according to the department training chief, Nick Walsh, Oliveri only encouraged them. In a blistering memo sent to city officials last September, Walsh said he had overheard Oliveri bragging about his close relationship with the union, saying it allowed him to do things “that are normally illegal and unethical for a fire chief to do.” (Oliveri did not respond to an invitation to comment.)

The episode that most upset Walsh was an attempt by Byer to get the department to hire his brother-in-law, who worked as a paramedic on nearby Whidbey Island. After two interviews and a background check, the brother-in-law was deemed “not hireable,” as two of the people who interviewed him later told the independent investigator. Still, Chief Oliveri pushed to keep him on a civil-service eligibility list beyond the usual time limit, to the consternation of many in the department. Walsh, the training chief, wrote in his memo, “Oliveri admitted that extending the eligibility list was unethical and wrong but stated that he had to do it because he did not want to sour his relationship with Byer.”

Six days after receiving the Walsh memo, the mayor of Anacortes fired Chief Oliveri. Three days after that, the city hired Dean to start the independent investigation in response to a slew of written complaints about the three union officials. One of those complaints, from Tom Nelson, suggested that the training controversy and the attempt to get Byer’s brother-in-law hired might even be connected. Nelson said that the brother-in-law had approached him and offered $10,000 if he would retire. “It was said kind of in jest, but I’m sure there was a kernel of truth in there,” Nelson told Red Canary Magazine. “The department had no openings, and he saw me as a possibility to leave.” (The brother-in-law declined to comment.)

By this point, vanSchaick was starting to emerge from the sidelines.

She didn’t share the union’s fondness for toughening up the training requirements, and the shift she represented on the Labor Management Committee, B shift, stuck to department policy in its training routines. For this reason, perhaps, vanSchaick was not invited to the meeting at which the three union officials lobbied Chief Oliveri about ladder training standards – even though all three department shifts are supposed to be represented at any meeting “of mutual concern.”

As soon as she found out about the meeting, held on the down-low in a station basement, she complained to the union on behalf of her entire shift, and she wrote a separate email to the city in which she said Byer had lied to her repeatedly and was fostering a “mob mentality” to make his members believe she had done something wrong by defending Nelson and Ringe, and was flipping the script to make the union officials look like the real victims.

As vanSchaick became more vocal, she knew she had to tread carefully, so she consulted closely with a senior union official in her region named Dean Shelton. He was the vice president of the Washington State Council of Fire Fighters and he agreed to accompany her to interviews with the independent investigator. As their text exchanges make clear, he also advised her on which union documents she should forward to the city and which she should redact. Not only was she at liberty to report instances of harassment and discrimination by union officers — as she and a number of her colleagues did in emails to the city’s head of administrative services — Shelton advised her it was “mandatory” to do so.

Shelton came to an Anacortes union meeting in early October 2020 and encouraged everyone to cooperate with the investigation. According to several people present, he also issued a warning against any attempt at retaliation against perceived whistleblowers. Shortly after Shelton left the meeting, however, Qben Oliver started railing at vanSchaick – as attendees later described in a flood of follow-up complaints to the city — and proposed a motion that anyone who divulged union business to the city should be brought up on charges of misconduct.

The proposal stirred the room to such uproar, particularly in the wake of Shelton’s warning, that Oliver backed off. (Oliver took issue with the word “railing,” saying it lacked context, but otherwise concurred with this account.) The city found the email complaints credible enough to place Oliver on four months’ paid administrative leave. Rebecca Dean’s investigation would later conclude that his motion had indeed been “an attempt to intimidate and retaliate against vanSchaick and Ringe.”

At this stage, vanSchaick had reason to think that she and her supporters in the department were making modest progress. Nelson and Ringe both joined her on B shift, viewing it as a refuge of sorts, and Byer soon announced he was stepping down as union president.

Things deteriorated quickly, however, after Dean’s report was issued in January and the union officers were able to see just how much information vanSchaick had passed along to the city in her emails, which the report reproduced in full. (The names of those lodging complaints against their colleagues, including vanSchaick, were redacted, but it was obvious to one and all who was who.) Oliver, far from being discredited in the eyes of the department, was elected the new union president while still out on leave and wasted little time in challenging the Dean report, even though it favored the union officers on the main discrimination charges. “My imagination isn’t good enough to come up with some of the things I was accused of,” Oliver told Red Canary Magazine. (The city, for its part, said it “stands by the findings of the Rebecca Dean report.”)

According to two senior firefighters who attended his union meetings, Oliver later gave his blessing to a move to expel vanSchaick and rallied his members to support it. (Oliver disputed this, saying he spoke only in support of firefighters “engaging in a good faith effort to exercise their rights.”)

The formal “notice of charges of misconduct” against vanSchaick was filed not by a union officer, but by an ordinary member of the Anacortes department named Mike Tribble, who had previously worked with vanSchaick in a different part of Washington. According to vanSchaick and others, the two of them had once been friends. Now, Tribble was all too willing to drag her through the mud, accusing her in a free-wheeling, less-than-rigorous bill of particulars of lying, unfairly trashing the reputations of union officials and putting “her agenda and political opinions above rational thought.” (By contrast, Dean, the investigator, found vanSchaick to be “an accurate reporter of facts.”)

VanSchaick struggled to take the charging document seriously because it offered little or no corroboration for Tribble’s accusations and made frequent reference to events, including the secret meeting between the union leadership and Chief Oliveri, at which Tribble was not present and, therefore, had no direct basis for accusing vanSchaick of lying about them. To vanSchaick, the whole thing smacked of retaliation and, as she subsequently argued to the IAFF, a violation of a Washington state law that specifically prohibits labor unions from expelling whistleblowers who complain about discrimination or other unfair practices. This was, vanSchaick said, Tribble’s way “to gain entry to a boys’ club of which he was never a part.” A lieutenant on vanSchaick’s shift later informed the IAFF that Tribble had told him, “I filed the charges, because if Ben [Qben Oliver] did, it would be seen as retaliation.”

VanSchaick found this line laughable, too – an indication that her antagonists were not only in the wrong, but they were none too bright, either. (Tribble denied making the remark or acting at anyone else’s behest, and insisted there was no “boys’ club” at the department.) The IAFF saw the charges in a different light, however, and dismissed an attempt by vanSchaick to have them thrown out ahead of a full “trial.”

According to the IAFF’s constitution, such trials are supposed to take place either in the accused firefighter’s home city or an adjacent community. Yet vanSchaick’s has been put in the hands of a local in Marysville, about 50 miles from Anacortes, where Dean Shelton is both union president and a battalion chief. At an earlier time, this might have looked like a positive development for vanSchaick. But, she says, Shelton abruptly dropped his previous support for her once the charges were filed, and now all she sees in the choice of venue is a glaring conflict of interest. Not only has she lost all faith that the proceeding will be fair; she has told the union she won’t be attending since she sees the trial as “no more legal than if you had invited me to a duel at sunrise.” Shelton did not respond to a request for comment. Ricky Walsh, the organizer of the trial, told Red Canary Magazine he saw no conflict of interest and insisted that Marysville had been “picked at random.”

“This is their process for crucifying someone who speaks up,” vanSchaick said. “This is the punishment. The trial itself is the punishment. People don’t want to go through what I’m going through, so next time they’ll back down. Is this against the law? From what I understand, yes. But to prove that, I’ll have to go through the process of bringing a lawsuit with my own money against my own local. Meanwhile, they are using my money, the dues I’ve paid month after month, to go after me.”

VanSchaick isn’t sure of her next move. But she is refinancing her mortgage and, one way or another, is determined not to back down. “As long as they keep pushing women like me out of the door,” she said, “nothing is going to change. As long as we keep letting these assholes drive us out, it’s going to continue.”

***

It’s not uncommon for large public unions to be riven by factionalism, in-fighting and occasional dirty politics. What makes the IAFF unusual is that, in common with its membership, it is top-heavy with white men and is viewed with suspicion, if not outright hostility, by Black and female members, who often establish their own separate advocacy groups and see the union not as a partner but as an obstacle to securing their workplace rights.

The pattern, these groups say, is that a firefighter like vanSchaick who complains about a perceived injustice ends up being blamed for making the fire department or the union look bad. The expectation is that firefighters, especially ones who do not fit the traditional role model of the tall, muscle-bound, white heterosexual male, will take any mistreatment doled out at the station house and remain silent about it.

Blaming the victim, she said, is second nature in the firehouse culture.

Regina Wilson, a former president of the Vulcan Society, which represents Black firefighters in New York City, described how a president of her IAFF affiliate once asked her if there was a way to reduce the number of discrimination complaints made by Vulcan Society members to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunities Commission because they were costing the union a lot of money in legal fees and tarnishing the reputations of the targeted firefighters. Wilson replied, “What are you telling me for? If people in firehouses weren’t such idiots and jerks, nobody would ever have to go to the EEO. Talk to the people who are causing you to have to spend the money in the first place!” Blaming the victim, she said, is second nature in the firehouse culture.

The Vulcan Society coat of arms, a group established in 1940 by Black firefighters who opposed racial discrimination. Photo found on the Vulcan Society Inc. website

When, in the 2000s, the Vulcan Society sued the New York fire department for claimed discriminatory practices in its entrance exams, it won the support of the Justice Department and eventually wrested a large settlement out of the city. But the New York union, the Uniformed Firefighters Association, sought to intervene in the case against the plaintiffs, saying it had an interest in safeguarding what it called “hiring based on merit.” The union is supposed to offer its dues-paying members protection against a hostile workplace, Wilson said, but too often the union itself is the source of the hostility, a breeding ground for “beliefs and customs and traditions” that do not see women or African Americans as equals.

Sometimes, that mindset translates into open animus – Wilson offered the example of a union officer throwing an African American’s steak dinner onto the ground before serving it. Sometimes it’s more casual cruelty, like forgetting to tell a union pharmacy which firefighters at the local are women, thus disqualifying them from receiving female-specific medications. “It’s hard,” Wilson said, “paying your money every month only to be ignored by the very people who are supposed to be giving you a service. Why should we put up with that? If I go to your restaurant, I’m not going to pay you while you spit in my food.”

“I don’t know of any woman who’s complained and gone on to have a smooth, easy career. The dudes we complain about get maybe a slap on the hand and the women get blackballed.”

When firefighters speak up about injustices, it can lead to some weird and unwelcome outcomes. One striking example is Melissa Kelley, a Los Angeles firefighter badly injured in 2004 when she lost her grip on a 35-foot ladder during a notoriously tough training drill known as the “humiliator,” which deliberately pushes firefighters beyond department best practices as a test of their strength.

Kelley, who was tired after returning from a live fire call, was pinned beneath the ladder and later diagnosed with a torn rotator cuff and seven damaged discs in her back and neck, but the captain overseeing her training refused to let anyone respond to her pleas for help. At first, the department was unequivocal: the captain, Frank Lima, had put the entire training crew at great risk, and his refusal to help had contributed to Kelley’s injuries.

Under union pressure, however, a six-day suspension was reduced to a two-day suspension and, eventually, to a written reprimand – “less than you get for losing a radio,” as Kelley later reflected in a Los Angeles Times interview. Extraordinarily, Lima proceeded to sue the department, alleging he was a victim of retaliation because he wouldn’t bow to pressure from his superiors to give women firefighters preferential treatment and convinced a jury to award him $3.75 million in damages. Today, he is the IAFF’s general secretary-treasurer, the union’s second-highest-ranking official.

Holly vanSchaick is under no illusions about what awaits her. Losing her union status won’t threaten her job security, and in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2018 Janus ruling she is still entitled to inclusion in collective bargaining agreements, even without paying dues. But expulsion will be a black mark on her in the workplace and will greatly complicate any attempt to seek employment with a different department. “Right now, as a woman in the fire service, my working conditions are toxic, and they are worse because of the IAFF,” she says. “I don’t know of any woman who’s complained and gone on to have a smooth, easy career. The dudes we complain about get maybe a slap on the hand and the women get blackballed.”

As a believer in the union cause, she finds this power imbalance particularly galling. She understands that the Democratic Party politicians she votes for are unlikely to fix the problem, because they rely on unions like the IAFF to bankroll their campaigns and cannot afford to alienate them — and that, too, galls her. “Labor and the Democrats are strongly aligned,” she said. “But if we continue to let the union do ugly things, we will be digging our own grave. We are the best argument the anti-union movement has against us.”

Pushing forward, whatever the cost, is the only counter-argument she sees. “As long as we continue taking their shit and shoving it aside so they don’t look bad, nothing changes,” she reflected. “And I’m not OK with it anymore. There’s no excuse for having only 3.7 percent women in the fire service. That’s shameful. It was 5.9 percent 10 years ago. If we don’t see this as a problem, we’re not looking.”

An earlier version of this piece cited the Dean report’s finding that Qben Oliver put Tom Nelson through the window entry and rescue drill for five days in a row. Both parties agree that Nelson was not required to perform the drill on five consecutive days, and the piece has been changed accordingly.

We also reported that Oliver’s motion at the October 2020 union meeting was later omitted from the meeting minutes. While there was a dispute over access to the full text of Oliver’s motion, further reporting has established that the motion is mentioned in some fashion in all versions of the minutes and that our original reporting was therefore open to misinterpretation. We have removed the reference to the minutes from the piece.

Help us sustain independent journalism...

Our team is working hard every day to bring you compelling, carefully-crafted pieces that shed light on the pressing issues of our time. We rely on caring supporters like you to help us sustain our mission. Your support ensures that we can continue to provide deeply-reported, independent, ad-free journalism without fear, favor or pandering. Support us today and make a lasting investment in the future.

What a work of fiction. Andrew Gumbel didn’t write this, Holly did. This entire ordeal has been a hit job and character assassination orchestrated by Holly to paint herself as a “victim” at every turn. This is ONE side of the story and obviously Andrew hasn’t done his job as an objective “journalist” because NO ONE on the other side of what happened is interviewed or quoted. Holly accepts not once ounce of responsibility or ownership in her part and has been in fact the aggressor and the most hostile person I’ve ever met. In 2 short years she has dismantled what used to be a small yet tight knit organization the respected and looked out for one another. Those days are gone. Holly’s done the same thing at the other 2 places she’s worked. Now she cries out her fairy tale to the press to destroy as many peoples reputation as possible and make herself look like some sort of hero. what a JOKE. No wonder no one has ever heard of Red canary collective.

The author responds.

Obviously, the commenter is entitled to an opinion, and it is certainly true that the events related in the piece have created divisions and some hostility in the Anacortes Fire Department. But it is factually incorrect to say no one “on the other side” of vanSchaick has been interviewed or quoted. Everyone mentioned in this story was given an opportunity to comment, and many took that opportunity. It is also incorrect to say that the piece relied on vanSchaick’s version of events to the exclusion of others, as the highly sourced and thoroughly corroborated piece itself makes abundantly clear.

SMFH! Great article, but it makes me sooooo angry! Twenty years in the fire service was enough for me and I’m grateful I made it to my pension… scars and all – many caused by similar experiences. As an optimist, I do think progress is being made, but sadly, at such a snails pace that, like all civil rights battles, it will NOT be corrected in our lifetime. Toxic, insecure and ignorant coworkers are ‘the problem’, NOT the folks unwilling to put up with their bad behavior. My biggest disappointment; too many coworkers quick to disparage others (pure insecurity), and even more disappointing, other’s willingness to believe their BS (vs. questioning the motive of the disparager). And, of course, it goes without saying, but I’ll say it…those who witness it and remain silent… truly disappointing! Holly VanSchaick, please don’t give up. I’m rooting for you!????

The AFL-CIO is the largest umbrella group of unions in the U.S. It is a self-aware organization that works to help its member unions understand that “we ALL do better when we ALL do better.” So much so that a former Exec. Vice President made this very clear statement in 2007: “The wonderful dream of the AFL-CIO will come true only when every member of our movement—black or brown or white, female or male, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or straight, immigrant or native-born, with disabilities or without—is heard, every member has a chance, every member has a voice, every member can rise to the leadership, every member is treated equally.”

I believe that there are many in the IAFF who agree. Every other year the IAFF puts on the Ernest A. “Buddy” Mass Human Relations Conference. Why? Because the IAFF wants to address the “good old boy” culture that creates problems like those that were addressed in the article.

That makes the IAFF “self-aware.” How do I know? Because I have taught at that Human Relations conference. The workshops at the conference are all about internal organizing around issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Somehow, the author either doesn’t know about this, or he believed it irrelevant to the story he was trying to paint about the IAFF from Washington State to New York City.

Is everyone in the IAFF or any other union on the “same page” about this notion? Not yet, but the leadership of the IAFF is working to bring more to the fundamental understanding that “an injury to one, is an injury to ALL.”

Holly, like many women in many workplaces, experiences a type of mysogyny and because she has had this happen more than once it likely has given her the drive to stand up for what’s right! I hope the IAFF takes responsibility for their actions and misdeeds instead of projecting them onto hardworking committed people like Holly. She is an exemplary human being and is being unjustly attacked for having ethics and morals. I’m 100% behind you Holly and all the women out there fighting for justice!

I believe it. I hope she prevails and paves an easier path for other women on the job.

Holly sounds a bit insecure and hysterical to me. Is she one of those people that cry wolf at every opportunity? It strikes me kind of funny that she has had these same if not similar problems everywhere she has worked. It sounds like she enjoys playing the victim. There are always two sides to every story, and considering her past history it certainly sounds fishy.

Stay Strong Holly. All women who seek to be more than doormats know your story rings true.

I’ve worked in male dominated industries my whole working career. I am all for women and minorities being treated equally in the workplace and I have found that through not drawing attention to myself, trying to build respect and trust from my fellow male workers, it has been largely great experiences. Many of them became dear friends and mentors. However there are very rare cases where someone takes full advantage of being a super-protected class and this sounds like one of those cases. I have seen this one other time in my life. For other women that try to follow someone like Holly in the industry, she has just set them 10 steps back. They now have to go into a work place where someone created a toxic work environment and everyone has been traumatized by it and they have to build back that trust and respect from their male counterparts. It sounds like Holly wasn’t happy with the investigation finding no wrong doing. This tactic of going to the media serves only to further alienate her and can’t be helpful in solving issues, communication with co-workers,and working as a team.