Out in the Tules

“Everything was water except a very small piece of ground.”

─ a Yaudanchi Yokut man

Frank Forrest Latta was interior California’s most important historian, a man cut from the same cloth as workaholic ethnographer John Peabody Harrington, oral history’s answer to musicologist Alan Lomax, and during the 1938 flood year, he decided to boat 400 miles from Bakersfield to San Francisco on the warm brown water. It was an impossible-sounding trip. No one had done it before, and no one has done it since. He wasn’t aiming for a record. He was publicizing the need to dam California’s swollen rivers to protect property and increase agricultural productivity during the state’s rapid pre-WWII growth.

At age 46, Latta was an experienced outdoorsman with two kids and a high school teaching job, and he spent his free time driving California’s back roads to interview thousands of settlers and Native Americans for his books and articles about frontier life. By the time he died at age 90, he’d interviewed approximately 18,000 people, published 3,000 articles and 14 or so books. His best known are the massive Handbook of Yokuts Indians, the definitive study of the Indigenous people who lived in the San Joaquin Valley’s arid lowlands, and Tailholt Tales, the record of one white 19th-century settler’s life with the Yokuts. This boat trip was a departure for him.

Standing 6’2”, with a face that alternated between quietly contemplative and childishly happy, he wore a short moustache and cut his dark hair tight in a military-type crew cut. Sometimes he carried a broad-brimmed hat. Sometimes he wore a sport coat and tie. Despite the summer heat, he stood in the boat on this day with his long-sleeved collared shirt tucked into his high-waisted trousers. Born and raised here in California’s San Joaquin Valley, he was used to the searing heat.

He’d equipped a 15-foot skiff, named The Alta II, with two motors, oars, navigational charts and camping supplies and painted the words “Kern Co. Special Bakersfield to Treasure Island” on its white wooden sides. Too arduous to complete alone, Latta took his 12-year-old son Don Latta with him and two high school students, Ernest Ingalls, age 16, and Richard Harris, age 17.

What The Bakersfield Californian called a “tremendous waste of water” had spread across the arid San Joaquin Valley that winter. Bakersfield’s Kern River had left 250 square miles of Kern County underwater, and flood damage reached into the millions. In March 1938, nearly an inch of rain fell in Fresno in one night. By April, melting Sierra snowpack breached levees near the cotton town of Corcoran and flooded 40,000 acres of farmland, and a 32-year-old named Robert Scutt drowned in a ditch after his boat struck debris. The few dams and canals didn’t control the rivers, so their floodwaters undercut roads and disrupted railroads, running hundreds of families from their homes and challenging the wisdom of settlers’ attempts to farm this saline desert. By June, those same rivers connected with marshes and lakes into a single hydrological system. A person could float from Bakersfield to the Pacific Ocean, though there was little reason to do so. Latta decided to try.

Starting in Bakersfield, Latta’s route took his team down the Kern River southwest to Buena Vista Lake near the town of Buttonwillow, where they floated north through Buena Vista Slough to Tulare Lake. Heading north through a confusion of marshes and channels, they passed over the Kings River alluvial fan into the San Joaquin Valley’s namesake river, whose freshwater shuttled them to Treasure Island in salty San Francisco Bay. These place names hardly add up to a useful mental image, considering how few of these hydrological features still exist. What’s important here are the water and superlatives.

Even with today’s dams and cyclical droughts, the Valley is defined by a continuous cycle of flood and drought. The process just looks different. Dams fill and water agencies dispense cubic feet to farms and cities. In the early 20th century, heavy snowfall would fill the rivers for a few good years. The land would fill with wetlands and ducks. Farmers planted crops as the waters evaporated, then the rivers would dry up for a few harsh years until the floods came again. Based on the urban and agricultural demands placed on it, the American Rivers organization named the San Joaquin “America’s most endangered river.” Ninety-five percent of the river gets diverted for irrigation, and 60 miles of its bed contain no water at all.

Until 1937, Tulare Lake had been dry for 13 years. The many levees that ringed the lakebed could no longer hold back the volume of snowmelt rushing from Sierra rivers, and the water spread across wheat and barley fields, washing away houses and tin sheds. Then summer descended.

In the marshes along the lake’s edge, heat turned the warm shallow water a vile green. Without depth or strong currents to circulate it, sediment collected. It grew thick with mud and algae. Frogs left clouds of squirming larvae, while fallen bulrushes decayed in the water that collected the bodies of innumerable insects. In October 1861, geological surveyor William Henry Brewer described the lake marshes as “unhealthy and infested with mosquitoes in incredible numbers and unparalleled ferocity.” Latta knew Yokut history, so he knew that by 1833, those same malarial mosquitoes had helped wipe out approximately three-quarters of the Native Americans’ population. Yet the monsoons of tule gnats, flies and mosquitoes that filled the air astounded him. It was impossible not to marvel at the lake’s dimensions, not just the water’s unbelievable volume but the grand scale of life and death. At sunset, millions of bats feasted on insects. During the day, the sun cooked the murky shallows, and its sulfurous smells traveled far on the breeze, like the thousands of pelicans, ducks and geese who carried stolen stalks of wheat from nearby fields.

But out on the deep lake, there was no vile green. No muck or feasting mosquitoes. Here the warm breeze blew fresh over the crews’ sweaty faces. Visibility was high. The scent of dry grass and moisture filled the air, and the cooler water took on a clean silver sheen. It reached 10, 20, 40 feet deep, and fish cut wide courses through the depths, swimming above sunken grain threshers and fences built by farmers whose respect for the great lake had diminished during its 13 dry years.

Despite the dangers, this day was surely one of the most wondrous. I imagine Latta jotting notes and studying his maps as Don, Ernest and Richard tried to keep the boat on a northeasterly course, feeling for a bottom that always lay beyond reach. Latta looked up to tell them to hang on to those paddles. Those were the only ones they had.

Desert winds often whipped up whitecaps, and in places, schools of fish ruffled the water like waves. The larger ones’ backs occasionally broke the surface, likely startling the boys as the boat rocked side to side. They wrapped their fingers around the wooden edges when they kneeled for a closer look. They didn’t want to fall in. What bigger creatures lurked down there? Latta told them not to worry; those were only suckers, chubs and possibly sturgeon, what the Yokuts called Caw’-cuts, but the boys’ hands gripped until their knuckles went white, because when they looked up they saw water in all directions. No shore. No reeds. Nothing but a single, shimmering, 360-degree horizon and the hazy shape of mountains hovering in the distance. To Ernest and Richard, the view looked like Pismo Beach, though somehow Fresno lay only 50 miles away.

In 2014, during the worst drought in California’s 500 years of recorded history, I got off Interstate 5 and stopped at the In-N-Out Burger in Kettleman City. A town of 1,400 people halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco, Kettleman City’s name reveals frontier ambitions that it hasn’t lived up to. When I asked the man cleaning the bathroom if he’d heard of the old Tulare Lake bed, he pinched his lips and shook his head. “Never heard of it.”

I said, “The old shoreline is supposed to be right around here somewhere.” He admitted he’d only lived around here for two years and was still getting his bearings.

Lake water had left marks on the land here. During average wet years, the lake often stretched 75 miles north and south, and 25 east and west ─ about 200,000 acres. Its wettest year was 1862, and it covered 486,400 acres, with depths reaching 41 feet. The thing is, Tulare Lake had no average year. It was a desert puddle in a drying period between ice ages. Some summers it shrunk to what the Lemoore Leader paper called “a huge mud hole,” leaving millions of rotting fish piled along the receding shore and locals collecting the live ones. Other years it stayed wet. Early gold miner John Barker told Latta that the lake in 1862 was “40 miles wide and 60 miles in length.” The part of Kettleman City that now served interstate travelers hamburgers and lattes sat safely atop what was called Orton Point in the 1850s. Named for Tulare Lake rancher Julius Orton, the point overlooked the Valley. It’s the first real rise of land modern drivers encounter heading north from Bakersfield. Although mosquitoes and the stink of dead fish would have reached it back then, water would not. But over the course of millennia, the mineral lake had left long horizontal stains somewhere around here, and if you looked, supposedly you could see them.

Out of curiosity and an obsessive drive to understand my native West, I’d rented a car and spent two weeks retracing Latta’s boat trip, in order to see the agricultural world that damming and flood control had created here. Thanks to water diversion and an average 300 days of sunshine a year, the Valley’s Class 1 soil supports over 250 crops, including everything from almonds to olives, grapes to kiwis, pistachios to pomegranates and 84 percent of the state’s dairy products. Americans who eat any of these have touched the San Joaquin. And yet, surprisingly few Americans have heard of this part of California. It isn’t just a part. Sandwiched between the Sierra Nevada mountains and the Coast Range, the San Joaquin Valley runs 265 miles through the middle of the state and averages 47 miles across, 75 at its widest ─ wide enough that you can’t see its edges on hazy days. You drive through it between LA and San Francisco. You cross it to reach Lake Tahoe and Yosemite. It covers eight million acres, houses over four million people, has some of California’s fastest growing cities, four of America’s five highest-grossing agricultural counties and some of the nation’s worst air pollution and is serviced by two large north-south highways.

I’d driven through the Valley for 20 years, heading between Los Angeles and more scenic northern locations, but I never really understood the place. Only after learning about Latta’s trip did I decide to make a concerted effort to. Equipped with photocopies of 1938 Bakersfield Californian articles, I drove through the Valley and visited numerous parks and cities, talking to everyone. On this, my fifth day traveling, I searched for Tulare Lake. I’d driven small roads on both sides of the Interstate and hiked up two hills, but I hadn’t found the colored bands on Tulare Lake’s old shore. Had I misread my source?

When I ordered a burger at the counter, I asked the young cashier if he’d heard of Tulare Lake.

He shook his head and smiled. “I’m sorry,” he said. “I don’t know where that is.”

At the neighboring Chevron station I asked a bearded customer in jeans, trucker cap and suspenders. He was stirring sugar into a coffee cup. “Tulare Lake?” he said. “Sounds familiar. There’s a lot of lakes around here. What is it?” It’s an old drained lake, I said, and briefed him on the history and location. He wasn’t from here. He lived in the Sierra Nevada northeast of Sacramento. “Oh,” he said, “it’s drained? Hmm.” His voice trailed off as he stared into space. “Tulare is a county. That’s why I heard that name. Tulare County. Sorry. No lake.”

As the sky darkened further, I pulled into the Starbucks drive-thru. “Hi, welcome to Starbucks,” said the voice in the speaker. “What can we get started for you?” I asked about Tulare Lake. “Um, yes,” she said. “Are you asking me where it’s at?” Yes, I was. “Well, you’re slightly on the wrong side of the Valley for that. You do need to go a little more towards Tulare, over, like, on the 43. So you’re going to travel north on 41 until you see Kansas. If you Google it or on Yahoo, then Kansas will take you to the 43. Tulare’s over on that side, so Tulare Lake ─ I don’t even know if it’s called that any more ─ but it’s over on that side of the Valley.” I was shocked. So far she knew more about it than anyone. Her name was Gina. She was the manager.

I pushed for more information. Was there still a lake there? “That I don’t know,” Gina said. “I haven’t traveled on that side for a long while.” She lived on the west side, in Avenal. Since she knew so much, had she ever heard anybody mention where you could see the lake’s old mineral stains here in Kettleman City? “Um, no,” she said, in a voice that signaled that I was either an idiot or I wasn’t listening, “cause we’re two hours from the coast, so I’m not sure where that shoreline would be.” She was losing patience. I explained the lake’s size in historic times, how it stretched from Corcoran to Kettleman City. “Oh, that I’m not sure.” I thanked her profusely and drove off.

She gave very specific details, but she still had it wrong. That was okay. Unlike the others, she at least made an educated guess that any lake with that name must be near the town of Tulare. It was a smart leap, and revealing. There is arguably no landscape in America that agriculture and water diversion have changed more fundamentally than the Tulare Lake Basin. In a 2004 report, the U.S. Geological Survey categorized Tulare Lake as one of California’s “discontinued lakes and reservoirs,” as if the West’s largest lake was an unpopular brand of frozen pizza. As I drove off, I kept trying to imagine what Latta would think of this world where the lake didn’t form the center of the local psyche, a feature which had loomed as large as the Sierras on early California maps and had dominated the lives of the settlers he’d interviewed in the early 1900s.

Adapted from The Heart of California: Exploring the San Joaquin Valley by Aaron Gilbreath by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. ©2020 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska.

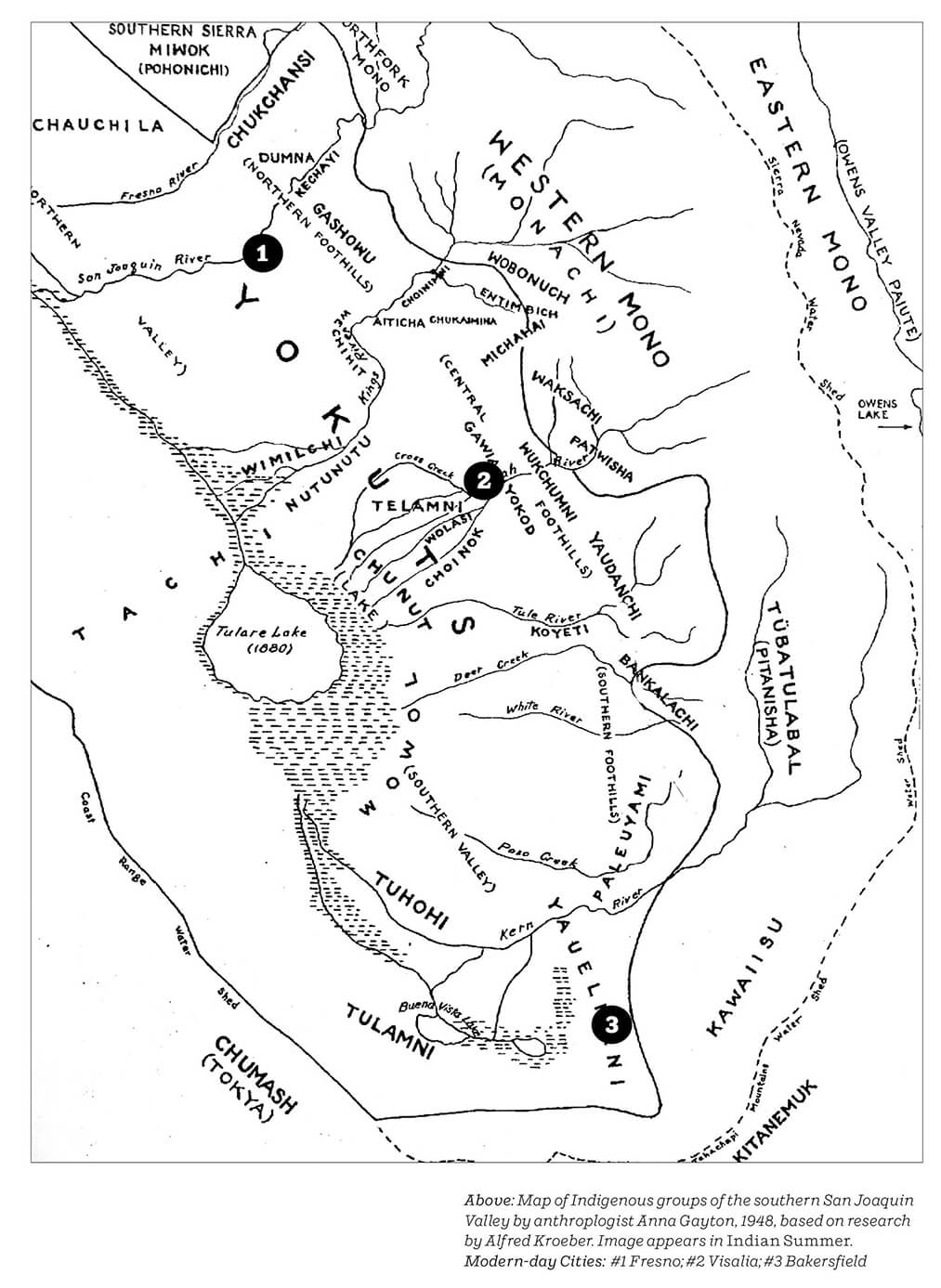

Map of Indigenous groups of the southern San Joaquin Valley by anthropologist Anna Gayton, 1948, based on research by Alfred Kroeber. Image appears in Indian Summer. Modern day cities: #1 Fresno; #2 Visalia; #3 Bakersfield.

Help us sustain independent journalism...

Our team is working hard every day to bring you compelling, carefully-crafted pieces that shed light on the pressing issues of our time. We rely on caring supporters like you to help us sustain our mission. Your support ensures that we can continue to provide deeply-reported, independent, ad-free journalism without fear, favor or pandering. Support us today and make a lasting investment in the future.