The Long Revolution

The 2020 Netflix picture Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution tells the story of groups of teenagers in the early 1970s who happen to be disabled enjoying summertime together at Camp Jened in New York’s Catskills. The Oscar-nominated documentary, written and directed by Nicole Newnham and Jim LeBrecht, features home-video footage, archival news media clips, plus more recent interviews conducted with some of the same characters viewers meet at the camp.

The documentary, whose executive producers include former President Obama and his wife Michelle Obama, makes a social-, health-, political-, economic-, civil- and human-rights, big-picture story into something that is also as simple as teenagers having fun. In the film, Camp Jened director Larry Allison says, pointedly, “We realized the problem did not exist with people with disabilities. The problem existed with people that didn’t have disabilities. It was our problem. So it was important for us to change.”

The original footage for Crip Camp was shot in 1971. The film came out in 2020. Somewhere in between, on July 26, 1990, the rest of us did change. Or at least, our laws did.

***

There’s a story that on the day the law changed — a standard, steamy, summer-sauna of a day in the nation’s capital — the White House organizers of the bill signing ceremony offered to move the outdoor happening indoors. The suggestion met with a strong no. The guests weren’t looking for special treatment. Never had been, really. Just the same treatment.

So the South Lawn ceremony begins. Dark suits for President George H.W. Bush and Vice-President Dan Quayle (remember him?). Among the other people on stage: Justin Dart, Jr., who later in this story will be favorably compared to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi.

One of the event’s speakers compares President Bush to President Abraham Lincoln for political courage.

That’s because Bush – “Papa Bush” as we’ll hear him called soon – was about to sign into law a historic piece of civil rights legislation: a law either two-plus years in the making (the original version of the bill was introduced April 28, 1988) or two-plus decades (when a slate of other civil rights acts were getting signed into law), or centuries or millennium. All are true.

Rev. Harold Wilke speaks now. “’Let my people go,’ you did decree O God, demanding that all your children be freed from the bonds of slavery,” the Reverend says. “Today we celebrate the breaking of the chains which have held back millions of Americans with disabilities. Today we celebrate the granting to them of full citizenship and access to the promised land of work, service and community.”

Of course, granting these rights doesn’t automatically signal universal change of hearts and minds. (See: Reconstruction, aforementioned Civil Rights Acts of the 1960s, etc.) Rev. Wilke must see that, too. He says, “Bless the American people and move them to discard those old beliefs and attitudes that limit and diminish those among us with disabilities… Amen.”

A good sermon is a tough act to follow, and this president wasn’t known for soaring oratory. Still, this is personal to him, and an achievement he will later claim as perhaps his most important.

“Three weeks ago we celebrated our nation’s Independence Day,” Bush says during his speech. “And today we’re here to rejoice in and celebrate another independence day, one that is long overdue. And with today’s signing of the landmark Americans for [sic – it’s With] Disabilities Act, every man, woman and child with a disability can now pass through once closed doors into a bright new era of equality, independence and freedom.”

Second row, front and center, a man raises a black-gloved left fist and pumps it euphorically as the president says – proudly, accurately, emphatically — “This historic act is the world’s first comprehensive declaration of equality for people with disabilities. The first.”

When you watch this clip on YouTube, you can turn on closed captioning for the hearing impaired. Thank you, Americans With Disabilities Act.

***

Another hot day, July 26, 2010. President Barack Obama similarly wears a dark suit, along with an American flag lapel pin. He is onstage on the White House lawn, at an event marking the 20th anniversary of the ADA, which he calls, “one of the most comprehensive civil rights bills in the history of this country.”

Just offstage, a sign language interpreter works. She isn’t Amber Galloway Gallego going viral interpreting Kendrick Lamar at Lollapalooza, but still. Thank you again, Americans with Disabilities Act.

“Today as we commemorate what the ADA accomplished, we celebrate who the ADA was all about,” Obama says, and you can hear that State of the Union-style narrative cadence. “It was about the young girl in Washington state who just wanted to see a movie at her hometown theater but was turned away because she had cerebral palsy. Or the young man in Indiana who showed up at a worksite able to do the work and excited for the opportunity but was turned away and called ‘a cripple’ because of a minor disability he had already trained himself to work with. Or the student in California who was eager and able to attend the college of his dreams and refused to let the iron grip of polio keep him from the classroom. Each of whom became integral to this cause.”

Obama praises some of the politicians who made the ADA possible. Among those are prominent 1990s-era Republicans. Shocking as it might sound today, given gerrymandered districts, Russian-bot armies and enduring right-wing, media-cult conspiracy misinformation, the passage of the ADA happened with elephants and donkeys partnering.

“It was generally a bipartisan effort,” Tony Coelho tells me.

Few people in the world had as much to do with the change in legal status for people with disabilities than Coelho. From 1979 to 1991, he was a Democratic congressperson representing Northern California’s East Bay. From 1987 to 1991, he served as majority whip – the member of the house leadership team responsible for counting and cajoling votes. He has epilepsy and faced discrimination, including being denied entry into the seminary, which he had thought was his calling.

“I sent a ‘Dear Colleague’ letter to every member of the House,” Coelho says about the ADA. “I said I was putting in this bill, and I talked about my disability, and I talked about the number of disabled people across the county. It was interesting to have members of Congress come up to me and say, ‘OK, I want to be on your bill. My mother, my father, my sister, my brother, my uncle, my aunt, my next-door neighbor has a disability. I don’t like the way they’re treated, and so I want to be on it.’”

These members couldn’t yet know the complete contents of the bill. They just knew that there was discrimination, Coelho says, and they wanted to be part of stopping it. Coelho recalls getting about 50 co-sponsors. Next session, when the bill was re-introduced and passed, there were many more.

Goliath politicians from both parties pushed the bill forward. They included Coelho; Sen. Bob Dole (R-Kansas), the Senate minority leader who later was his party’s presidential nominee; Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah); then-Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-MA); Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa); Sen. Lowell Weicker (R-CT); Rep. Steve Bartlett (R-Texas); and Rep. Steny Hoyer (D-MD).

Dole lost a kidney and the use of his right arm when he was shot during World War II. Kennedy had a sister with an intellectual disability — made horribly worse by the decision to give her a prefrontal lobotomy. (Kennedy’s aunt, Eunice Kennedy Shriver, founded the Special Olympics in 1968.) Harkin’s brother was deaf, and both he and Tom spoke sign language. Hatch had a brother-in-law with polio. Weicker had a son with Down’s Syndrome. Attorney General Dick Thornburgh was also a key participant in the ADA process. His son had suffered a brain injury. And, one of President Bush’s sons, Neil, is dyslexic.

None of this is surprising, given the estimate that one in four of all Americans live with a physical and/or intellectual disability. The estimates change over time, in part as the definition of what is a disability evolves. Still, passing the ADA was far from a fait accompli. The Equal Rights Amendment, for example, was written in 1923 and Congress passed it in 1972. It still hasn’t made its way into the Constitution.

In a 2019 oral history project interview with the LA84 Foundation, which I co-produced, Deborah McFadden spoke to my then-colleague Wayne Wilson and to the Olympic and Paralympic journalist Alan Abrahamson about her work as an adaptive sports and Paralympics advocate, and about being the mom of three kids including two Paralympians. She spoke, too, about the 12 years she herself had once spent unable to walk and her work as U.S. Commissioner of Disabilities from 1989 to 1993.

In the interview, McFadden recalls how President Bush set a big-picture goal and then left the details to her and others. “He said, ‘Here are the premises: Basically, I want you to improve the lives of people [with] disabilities. And how you do it, I don’t care. I want them improved.’”

(She says Bush “had a couple of things that he didn’t want, like fetal tissue research. ‘Can’t support that.’”)

McFadden continues. “So, a number of us talked, said, ‘We need something that’s all encompassing.’ ADA was the law that was created to be all encompassing and to elevate people to the equal right that so many others had fought before us… These were the things we were asking for, but we were those that lived in the shadow’s of life,” she says. “And, so, coming out of the shadows was hard for society because you’re better off in the shadows where we don’t have to deal with you.”

The bill required negotiation, listening and compromise. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce supported the ADA, but certainly not every office and store in the nation was thrilled. “There was a recognition of the need to address the legitimate concerns of business, and so they engaged in good faith with the disability community,” Bobby Silverstein says. “Because of that, I think we had a pragmatic bill that did the appropriate balancing and recognition of rights and legitimate concerns.”

Silverstein is a principal in a Washington, D.C. law firm, and former staff director and chief counsel to the Senate subcommittee on disability policy. He was Harkin’s chief disability aide and proved to be an extremely influential behind-the-scenes player in the birth of the ADA.

“The original version bill recommended by the National Conference on Disability had a provision that said that businesses had to provide reasonable accommodations unless they ‘threatened the existence of the business,’” Silverstein continues. “That sounds like a bankruptcy provision, and they said, ‘That’s not OK.’”

So, legislators changed the wording. “We ended up with ‘undue burden, significant district difficulty or expense,’” says Silverstein.

The day the ADA passed the House, McFadden remembers being in the gallery. She looked around and saw people debating the bill. “For the first time I thought, this is a microcosm here right now of whom this law will affect,” she says. “And, it wasn’t just people with disabilities, but it was the family members, the friends. It would change life forever. So yes, compromises were made. Things have happened, but what it says is, ‘We belong in society with all the rights that everyone else has.”

David Davis is the author of, most recently, Wheels of Courage: How Paralyzed Veterans From World War II Invented Wheelchair Sports, Fought for Disability Rights, and Inspired a Nation. The book was published in 2020 to capitalize on interest in the Paralympics, but the global pandemic led to the Olympics and Paralympics being postponed. (As of this writing, they are scheduled to proceed this summer, but a relentless and mutating virus may halt that.)

Davis’ book is a deep dive into the lives — athletic and otherwise — of paraplegic and other disabled people, as well as the innovative doctors who worked with them. The book focuses on pioneering wheelchair basketball teams with names such as the Flying Wheels and Rolling Devils.

The Rolling Devils team from Naval Hospital Corona with John Winterholler (center, seated) and Gene Fesenmeyer (far right).

Photo courtesy of Debrah Harms and the Winterholler family,

The book opens in March 1948 with a game at Madison Square Garden, in front of more than 15,000 fans. Later, there are parties with celebrities, advisory work on Marlon Brando’s debut film, barnstorming tours of the country to play and defeat able-bodied athletes as well as other nascent teams of disabled players, visits to Capitol Hill to lobby for disability rights, the founding of the Paralyzed Veterans of America organization, and plenty of media attention. Like when star player Jack Gerhardt appeared on the cover of Newsweek, in uniform, holding a ball, in a silver wheelchair that looks like it was polished five seconds ago, and then polished again.

Davis, in a recent interview, compares the players to another athlete and pioneering American icon of that era: Jackie Robinson. “They took paraplegia out of the shadows,” Davis says. “They brought it to society, and not necessarily like in your face, but in a way that said, ‘Look, we’re here. We’ve survived the worst of war. We’re going to live a normal lifespan.’”

Their bequest is vast. “They prove the efficacy of rehabilitation and rehabilitation medicine, which was very much in the shadows,” Davis says. “They prove that people with disabilities could not only go up and own a basketball court, but could have a family, and go and get a job, and could be a productive member of society… This had never really been achieved before. Because people with disabilities were shown and stigmatized and considered less, and these men proved otherwise. The courage they had was phenomenal, and the vulnerability they had to deal with, falling out of their wheelchair in the middle of Madison Square Garden with their urine bag, that’s not so easy. And yet they climbed back into their wheelchair and kept going.”

Davis contrasts the Newsweek cover with the way four-term President Franklin Delano Roosevelt hid his disability. “FDR had polio as a young man. He refused to be photographed in a wheelchair,” Davis says. “Why? Because it showed weakness. There was this stigma.”

Davis points out the difference between FDR’s decision and just a few years later, crowds coming to see wheelchair basketball games. “I think that’s an opening salvo in terms of the march to the ADA.”

Andy Imparato, executive director of Disability Rights California and former president and CEO of the American Association of People with Disabilities says, “The ADA was the product of a civil rights movement and then a growing disability cultural identity — all these other things that are the product of that. But the catalyst is not the law. The catalyst is the movement. And so in some way the ADA is like a Brown v. Board of Education. Brown didn’t happen by accident.”

That cultural identity has grown and evolved. Some of the people interviewed for this story talk about disability justice, rather than disability rights. One brings up the “10 Principles of Disability Justice,” which you can find online and which range from intersectionality, cross-disability solidarity and leadership of those most impacted to anti-capitalism and collective liberation. (A sample: “Anti-Capitalist Politic: In an economy that sees land and humans as components of profit, we are anti-capitalist by the nature of having non-conforming body/minds.”)

***

According to the U.S. Department of Labor website, “The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities in several areas, including employment, transportation, public accommodations, communications and access to state and local government’ programs and services.”

Some of the more visible results of the law include ramps into businesses, wheelchair-accessible doors, curb-cuts, accessible restrooms, volume control on pay phones in the past and now accessibility features on smartphones, people not being denied jobs, people being able to join school sports teams — and go to schools in general — and so much more.

World War II veterans-turned-pioneering-wheelchair-basketball-players practice at Birmingham Hospital in Van Nuys, California, around 1946.

Photo courtesy of the Rynearson family

After the ADA passed, a couple of U.S. Supreme Court decisions in 1999 and 2002 chipped away at the scope of the law. In one case, the majority of justices essentially ruled that disabilities had to be visible and couldn’t be correctable.

“In other words, physical disabilities were the only thing the ADA covered,” Coelho says. “Well, that’s absolutely not true. I was one of the main authors, and I was doing it in regards to epilepsy. That was in all my testimony, that was in all my letters. The Supreme Court just ignored that. And so I was meeting with the Epilepsy Foundation board [which he chaired, having left Congress] and convinced the board to have us lead the fight in regards to the ADA Amendments Act.”

Coelho’s connections and passion proved invaluable, even from the relative outside. He says he heard that there was opposition to this legislative branch fix from a high-level President George W. Bush administration official. “So I went down to Houston and met with Papa Bush,” Coelho says. “I told him that I was hearing there were efforts to veto it, and is there any way that he could help?”

Who was opposed? Bush asked Coelho. “I hemmed and hawed and finally said, ‘Well, I’m told it’s [Vice-President] Dick Cheney.’ So he presses the button on the phone to his chief of staff and said, ‘Get me the chief of staff to the president.’ This individual gets on the line and [Papa Bush] says, ‘I understand that Cheney is holding up the ADA Amendments Act, and there’s a threat of a veto and so forth. I just want you to know this is important, and you know, this is the L-word as far as I’m concerned.’”

“There actually is somebody who is known as the Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Gandhi of the disability rights movement,” Silverstein says. “And that’s Justin Dart, Jr. He was the visionary of the movement.”

Coelho continues, “When he got off the line, I was panicked because I thought the ‘L-word’ meant ‘liberal.’ And so I delicately said to the president, ‘What did you mean by the L-word?’ I’m thinking, this is just going to be awful. And he said, ‘Legacy, it’s the legacy. And I hate that word. And everybody knows when I say L-word, I mean legacy.”

Legacy preserved. The Americans With Disabilities Act Amendments Act of 2008 passed and was signed into law by President George W. Bush, restoring more of the original inclusive intent of the ADA. “When you think about the ADA,” Silverstein says, “You put it in the same category as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act.”

President George H. W. Bush Signs the Americans with Disabilities Act, 07/26/1990 / Photo from the George Bush Library, College Station, Texas

Were the amendments as important as the original ADA? Is this a Bill of Rights to the U.S. Constitution analogy? “I would not put the amendments in that category,” says Silverstein. “They would just be simply clarifications of congressional intent that was screwed up by the Supreme Court decisions. That’s a footnote. It’s not in the same category as… the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968, which was probably the first step because that required that federal government buildings be accessible. Then we have Section 504. And then we have the ADA.”

Section 504 of the Federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973 prohibited discrimination against people with disabilities by federal agencies and programs that receive federal dollars. This wasn’t all-encompassing of private companies and organizations, the way the ADA eventually would be, but it was progress. While 504 was technically the law, no enforcement was possible until a series of regulations were developed and put into place by the then-U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Nothing happened during the final days of the Richard Nixon presidency, throughout the feckless years of the Gerald Ford presidency, and into the first few months of Jimmy Carter’s term.

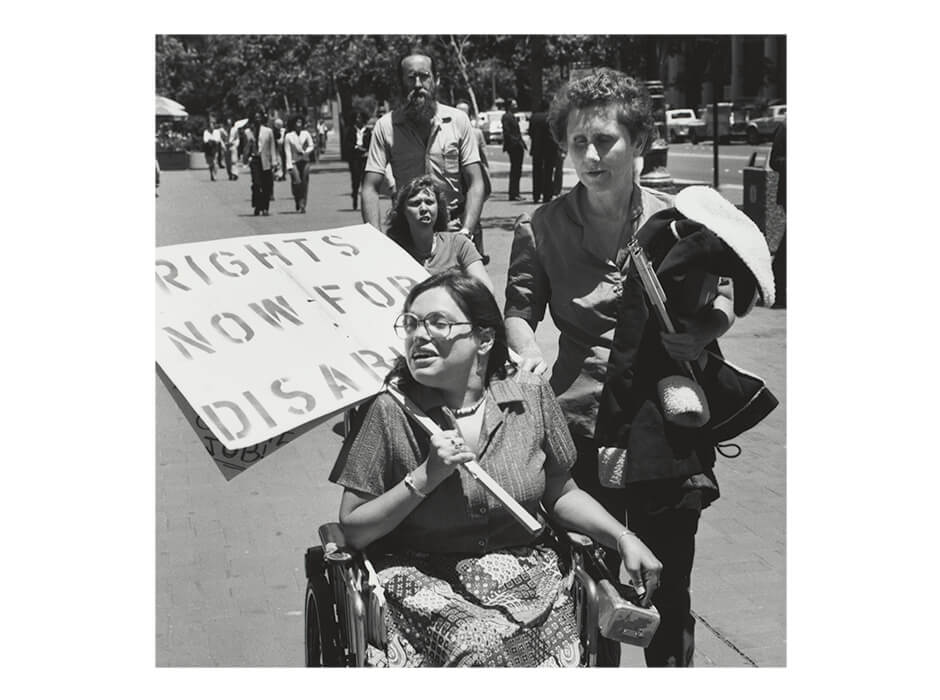

When — or for most people, if — you think about Section 504, it’s likely in connection with the occupation of a federal building in San Francisco by disabled-rights-movement activists in 1977. (Nearby Berkeley, along with University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, were epicenters of disability rights.)

Led by people such as Judy Heumann — a leading activist who would go on to serve in the Bill Clinton and Obama administrations — disabled protestors and their allies — the Black Panthers and Gray Panthers brought food, for example — occupied the building for 25 days, calling attention to the still un-enacted Section 504 of the federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Heumann and others in the group left midway to go to D.C., where they stayed until the trip produced results. It didn’t take long. On April 28, 1977, the Carter administration said yes to 504.

The occupation of the federal building notwithstanding, there apparently weren’t too many other iconic media moments in this movement. Andy Imparato of Disability Rights California names two. “One was the Deaf President Now protest at Gallaudet [University], which happened in 1988, which was pretty high profile for a week,” says Imparato. “And there was the Capitol Crawl. But those were like blips on a screen compared with very high profile stuff that happened around civil rights.”

The protest at Gallaudet University, the storied D.C. school for the deaf and hard of hearing, stemmed from never having in its 124 years a university president who was deaf. The student-led protest changed that and Dr. I King Jordan was hired in March 1988.

Shocking as it might sound today, given gerrymandered districts, Russian-bot armies and enduring right-wing, media-cult conspiracy misinformation, the passage of the ADA happened with elephants and donkeys partnering.

The Capitol Crawl in March 1990 saw some 60 people with disabilities — including an 8-year-old — abandon their wheelchairs or other mobility devices, and make their way up those 78 famous marble steps to the Capitol Building. No one wants to be lionized or presented as a superhero for just going from point A to point B. So I’ll just say, find yourself a clip of this protest and see for yourself.

(Side note: Somewhere on the endless list of reasons why the failed, traitorous insurrection of Jan 6, 2021 is so abominable, is that for a long time moving forward, that’s going to be all anyone will associate with the Capitol steps.)

***

It stands to reason that the people who were directly involved in the writing, passing and signing of the ADA consider it to be such an extraordinary achievement. How about for people who were kids – or not yet born – back in July 1990? They are the “ADA generation,” Imparato calls the latter group.

“It did what it could at the time,” Taryn Williams, managing director of the poverty program at the Center for American Progress think tank, says of the ADA. “It was a transformative sort of landmark civil rights legislation meant to improve the lives of people with disabilities, but as society has evolved we know that there is still work to be done.”

Williams, who lives with inflammatory bowel disease and arthritis, worked at the federal level on issues related to disability employment. “Perhaps by the nature of my work, both at CAP and also the decade that I spent with [the government], I have always sort of thought about it with respect to what is the unfinished business of the legislation,” says Williams. “I would never want to presume to speak for someone like Tony [Coelho] or Senator Harkin and many of the folks who were there really in the trenches fighting to get this law passed. But when I think about the ADA and where we are now, I think of two things: one is employment… and the second is related to community integration.”

Williams and others, including Silverstein, mention issues of integration in the tech world, including a lack of equity in accessible websites and apps.

A literally life-and-death issue comes up often as well in interviews with disability activists, as the pandemic threw into spotlight the idea of rationing health care, and determining whose lives are prioritized if a hospital is overrun by victims of the virus. (Side note: The ADA gave new rights to AIDS and HIV patients during the early-ish days of that epidemic.)

“There are many institutions — government, non-profit and private — that routinely flagrantly and blatantly violate the ADA… And it certainly does not mean the disabled people who are at the margins of the margins have ever enjoyed the full protections of the ADA.”

What else still needs to be changed? Lydia Brown is an advocate, organizer and lawyer for disability justice. They teach at Georgetown and is the Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network’s director of policy, advocacy and external affairs. Brown was born after the original ADA passed.

“The ADA means that in theory, I have certain legally recognized civil rights as a disabled person that applied broadly,” Brown says. “And generally that I would not have had, had I grown up in a world without the ADA in existence. At the same time, as we all know, just because something is a law, it does not mean that it’s actually followed, particularly by those who hold the most power, the most privileged, the most resources, and who have the most to lose. There are many institutions — government, non-profit and private — that routinely flagrantly and blatantly violate the ADA… And it certainly does not mean the disabled people who are at the margins of the margins have ever enjoyed the full protections of the ADA.”

So did the ADA at least provide a useful framework? Or is it considered toothless and irrelevant to new generations?

“I’d hardly call it toothless. I would call it underenforced and I would call it limited, but not limiting,” Brown says. “The ADA can be an incredibly useful and important tool in our arsenal. However, the ADA is not going to get us to liberation…. The ADA can help move us a little bit in that direction, however. You can enforce it, right? And that’s still not going to change underlying values, beliefs or attitudes. I always tell people this: You can’t legislate morality.

“The ADA was passed more than three decades ago, and yet much the same has remained in the way of how society understands and responds to disability as something that deserves charity or pity as something that is horrific grotesque, disgusting, shameful; as something that is a blight or a burden societally or culturally. Those attitudes and beliefs have not changed.”

***

OK, let’s end back where the ADA was born, on that hot, historic July 26, 1990 day on the White House South Lawn. One of the other handful of people on stage along with President Bush and Vice President Quayle was Justin Dart, Jr. The president seems to refer to Dart with affection, calling him “Jus.” Two decades later at the anniversary event, President Obama refers to Dart posthumously as “the father of the ADA.”

When I speak with Silverstein, I speculate there isn’t a Rosa Parks or MLK equivalent in this story. Silverstein corrects me immediately. “There actually is somebody who is known as the Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Gandhi of the disability rights movement,” Silverstein says. “And that’s Justin Dart, Jr. He was the visionary of the movement.”

David Davis, the Wheels of Courage author, shares Dart’s backstory: “He was an interesting guy. I believe he had polio when he was [18], but he was fortunate to be in a very wealthy family so he had the means, like FDR, to get the best medical care and rehabilitation services.”

“They prove that people with disabilities could not only go up and own a basketball court, but could have a family, and go and get a job, and could be a productive member of society…”

Dart’s grandfather started the Walgreens pharmacy chain, and his father ran various companies. In the early ‘60s, Dart was in Japan. The 1964 Olympics and Paralympics were held in Tokyo, and Dart attended. The Paralympics were relatively new, having grown from the Stoke Mandeville Games launched in England in 1948 by Dr. Ludwig Guttmann, a German-born pioneer in the concept of treating paralyzed people as whole people, and pushing them towards exercise and independence. Previously, as Davis reports, most paralyzed vets died within 18 months. His book details how a common treatment — if you will — at the time was placing paralyzed people in full body casts, more or less a living coffin, and essentially waiting for them to die.

In Tokyo, the Olympics were an opportunity to showcase the new Japan, less than 20 years after Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Japanese surrender in WWII. The Paralympics were still an afterthought, but 378 athletes from 21 countries participated. Dart donated wheelchairs for some of the basketball games, Davis recalls. He watched powerhouse Team USA take wheelchair gold. Afterwards, “Dart hires one of the athletes, Dick Maduro [to coach], and he and his wife form a team that would play under a Japanese tupperware company logo. They played all over; they helped normalize disability.”

When Dart moved back to Texas, he became involved in the greater cause. “In the late `70s, early `80s, he becomes one of the key figures in the transition to how to get the ADA passed,” Davis says. “He’s a conduit. He’s a key figure because, yes, on one hand he represents people with disability, but he also has — through his father’s connections — connections with the Republican party powerhouses including Ronald Reagan and George Herbert Walker Bush.”

Silverstein notes that when Dart went to Japan, he gave up his vices, read and learned, and came back to the U.S. as that visionary. “He basically spent 24 hours a day, seven days a week, going around the country with respect to ADA, collecting Discrimination Diaries,” Silverstein says. The travel was apparently at Dart’s own expense and done while he served as co-chair of the Congressional Task Force on the Rights and Empowerment of Americans with Disabilities.

“He was the person who had the vision and the moral backing to galvanize the community,” Silverstein says. “And what Justin did, intentionally, is he wore a cowboy hat to every event, to kind of say that somebody was watching over the proceedings, to make sure that we never compromised basic, fundamental, human and civil rights.”

Dart wore that trademark hat to the ADA signing ceremony. At long last for him, and for all the activists, advocates, legislators and everyday Americans who have a disability or disabilities or care about someone who does, the law of the land was finally more fair.

Help us sustain independent journalism...

Our team is working hard every day to bring you compelling, carefully-crafted pieces that shed light on the pressing issues of our time. We rely on caring supporters like you to help us sustain our mission. Your support ensures that we can continue to provide deeply-reported, independent, ad-free journalism without fear, favor or pandering. Support us today and make a lasting investment in the future.

An excellent article!