Up Through the Soil

Click on each image for photo credit and captions.

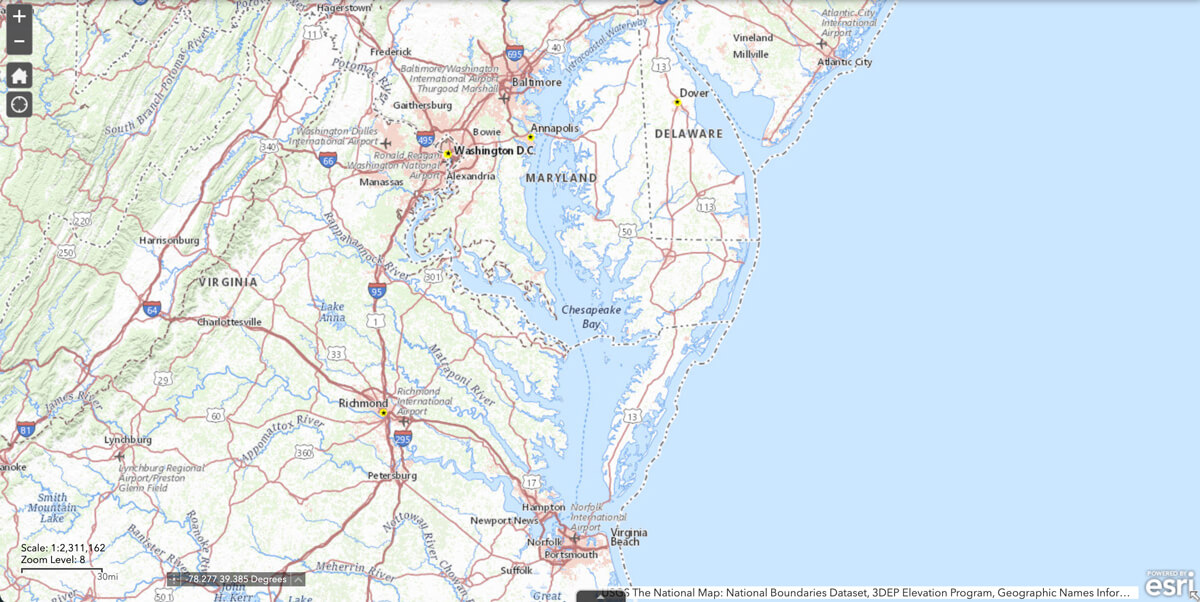

Sunlight reflects off the light chop on Chesapeake Bay as Crisfield Harbor, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, fades from view. Narrow, jagged spits of land on the starboard side of the ferry boat Captain Jason II are full of marsh grass swaying in a mild breeze as the captain guides the boat toward Smith Island.

On board on this cold January day is Ronald L. Williams, Jr., a sixth-generation Washingtonian, farmer and waterman who is reclaiming his ancestors’ agrarian roots by bringing to the island a locally integrated seafood- and produce-harvesting and -distribution business — and more: In addition to growing, aggregating and delivering food, he’ll function as a tourist-friendly innkeeper as well.

Williams has driven three hours from his home in Washington, D.C. to make this 10-mile, 40-minute ferry ride. His mission today is to survey a dilapidated 19th-century farmhouse where he plans to co-locate the operation with a bed and breakfast, among other amenities.

It’s an audacious plan that has been evolving over time, as he has acquired property on land, water and the island, and developed a farm-to-table enterprise that reaches all the way to his hometown.

After meeting with contractors who will help him renovate the farmhouse, Williams plans to scout for a dock suitable to bring in crabs, oysters and perch that he pulls out of the bay so he can combine them with fresh catch he purchases wholesale from local watermen, then ship it all to Crisfield to sell there and at fish markets in D.C. and suburban Maryland.

In Crisfield, Williams will do the same thing in reverse with a facility near the harbor to consolidate wholesale produce with the produce he grows on property he owns in surrounding Somerset County, where he uses conventional methods to grow collards, kale, carrots, apples and peaches. (Closer to D.C., in neighboring Prince George’s County, he also hatches 2,500 chicken eggs a year from his family’s farm in Brandywine, MD.)

Once he boxes up the produce, he will ferry some of it to sell on Smith Island, where there is no grocery store, and truck some of it to D.C., which is plagued by food deserts.

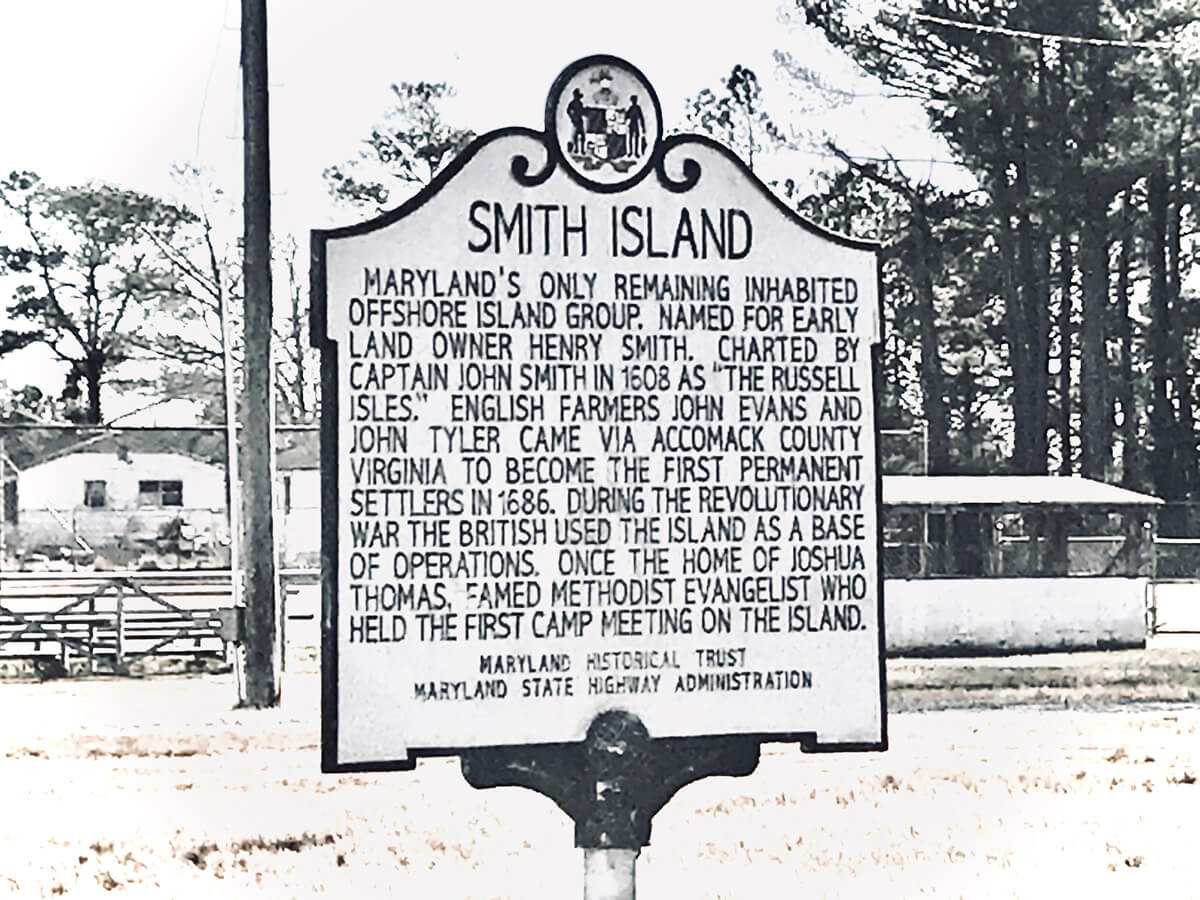

Smith Island is at first glance an odd choice for Williams to make his stand. It’s the first permanent settlement established by the British in 1686 and the fewer than 300, almost-entirely white residents here speak in a slow drawl that is neither Elizabethan nor recognizable as modern English.

“I don’t get in anyone’s way,” Williams says, “due to the color of my skin.”

That doesn’t mean he looks the other way where matters of race are concerned. Williams is the first to say he’s got a bit of a chip on his shoulder, and he cops to being confrontational sometimes. But he takes racial slights and offenses, and channels them into his drive to succeed.

His success as a waterman and a farmer, and his ambitious vision, is not in spite of his Blackness, he says — it’s because of it.

On Smith Island, Confederate flags and Trump signs are commonplace, Williams says, but he has not encountered any problems so far. Though he does not speak in the same dialect as the residents do, they all speak the same economic language: Everyday life is transactional, Williams says. The island runs on goods, services and handshake deals. There are no bank machines, and anything but cash is frowned upon.

So far, he seems to fit right in.

Coming into the harbor, we pass a series of small docks and crab shacks, the nation’s first post office, its first fire station and the occasional American flag. Williams steps off the Jason II and waves to familiar faces as if he’s been here for years.

“These folks understand two things,” Williams says of his new neighbors. “Blue crabs and green cash.”

Life closer to D.C., the Maryland suburbs and the farming communities of the Delaware-Maryland-Virginia Peninsula (“Delmarva”) is not as simple.

An older generation of white family farmers is dying off without any succession plan in place. The small farm-to-table movement is alive, but Williams says it is run by white sustainability “congregants” who talk about inclusion more than they practice it.

The larger family-farm model, however, is none of his concern. Nor is the trendy urban agriculture or certified organic movement. Though his holdings are yet relatively small, Williams is a conventional farmer who peels back the sod, tills the soil and plants seeds in row beds. He lays down plastic ground cover to conserve soil moisture and uses synthetic herbicide once the crops start to grow.

The newer method is to germinate crops in a hoop house, then transplant them in wooden-encased raised beds into crop rows. Williams says that method is unsanitary. “For me it’s a soil issue,” he says. “They don’t peel back that sod layer. They don’t want to till that soil. That’s how you get to your nutrients and break down any impurities. Somerset County has the best soil on the [Delmarva] Peninsula.”

His harvesting and distribution model is old-school as well: He harvests his yields and delivers them straight to table or market — there are no warehouses, storage facilities or intermediate delivery points.

The most important thing for Williams is staying independent and being self-sufficient. He has no partnerships or alliances. For now, he leases trucks for transport and boats for fishing, but he owns 14 acres of land on eight separate pieces of property.

His approach is based on diversification of product and lines of business, and accumulation of what he refers to as “generational wealth,” something that has been inaccessible to Black farmers.

Is this what sustainable farming looks like?

Williams scoffs at the term; sees it as an overused label. If it means practicing farming methods that are profitable, environmentally sound and good for communities, then yes, he is able to make a living by farming, fishing and integrating the bounty of the Chesapeake watershed with a healthy respect for the land and the water.

He also maintains his business at a manageable size and scale, and is neither over-reliant on credit or on others.

He knows crop numbers, pasture fields and crab-trap coordinates for a complete range of produce, eggs and seafood that he delivers to Black communities in the D.C. area that are starved for fresh and healthy food.

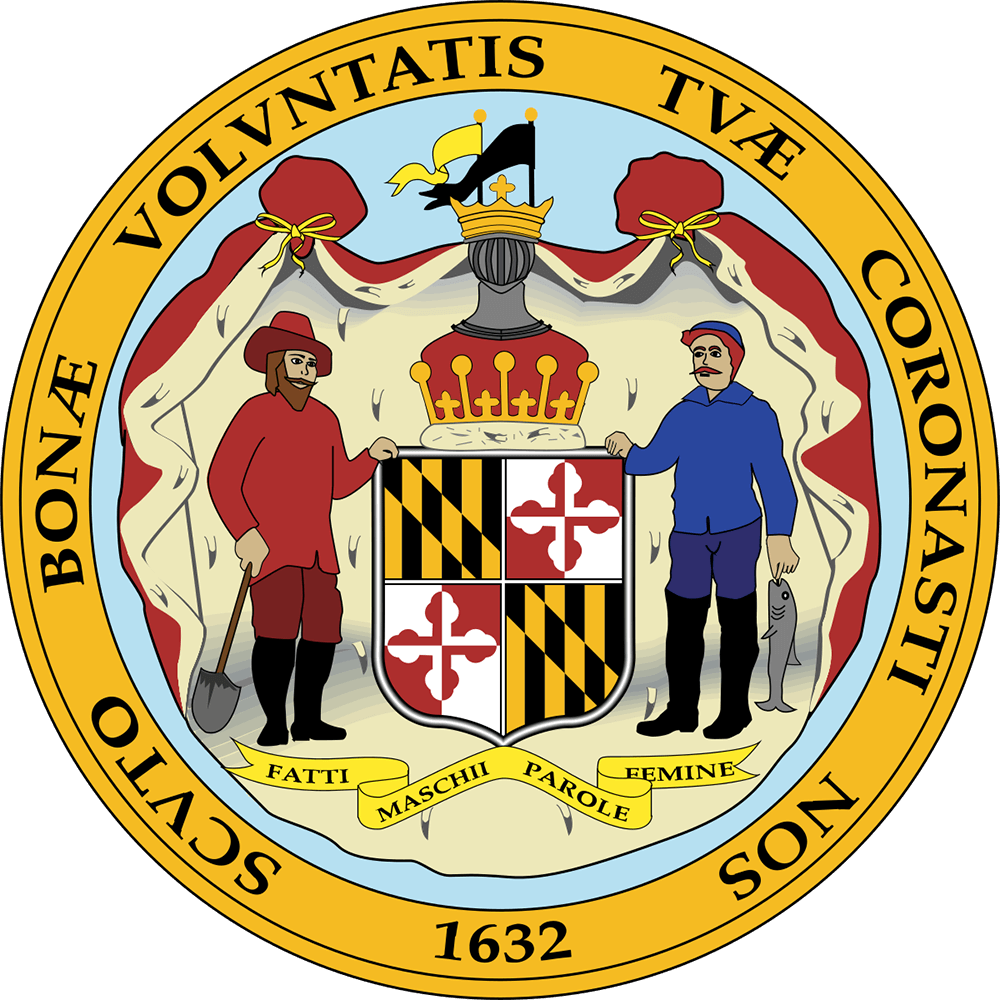

For a simplified analogy, he points to the state seal of Maryland, which displays a farmer with a shovel in his hand, and a waterman with a fish in his hand. His goal is to embody both.

“My overall operation takes a shot at the traditional agrarian farming model: soybeans, corn,” says Williams. “But we also are a diversified operation that capitalizes on the history and location of the Chesapeake Bay.”

He sees his inspiration for these pursuits as a legacy and a birthright.

“I want to do things my own way, because of what stories were birthed, the people that fought for freedom and empowerment of Blacks, and the economic power we wield now because of their past sufferings.”

The question of whether Williams can realize his version of the American Dream is central to a larger one: Can other Black farmers and fishers realize theirs as well or do they have to settle for second-class status in the mainstream farm-to-table movement?

***

The history of Black entrepreneurship — certainly in the South — is the history of agriculture. But in the post-Civil War era, it took decades for freed slaves to go from “40 acres and a mule” and sharecropping to actual property ownership.

By 1900, Blacks in the South owned or partly owned more than 12 million acres of usable farmland, mostly to grow cotton, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Even then, Jim Crow laws allowed white business owners to inflate interest rates on farm loans. Crop diversification afforded Black farmers cheaper debt, but they still lacked equal access to research and technology.

Ownership peaked in 1920, when the Census of Agriculture counted more than 925,000 Black farmers, comprising 17 percent of those registered in the United States. By 2017, that number had shrunk to 35,000 — less than 2 percent of those registered. (See “A Grievous Harvest” by Dean Kuipers.)

When Williams decided to go into farming, he did so on the shoulders of his ancestors and his own family members, who have been chicken farmers going back to the 1960s.

“When we were kids we’d run around and chase the chickens, and it was just fun. But when I was 21, my uncle said, ‘Nephew, you gonna come down and work on the chicken farm?’

“It gave me my first education in commerce, physical education, enterprise development… Looking back, it was a training ground for the entrepreneurial efforts I’m undertaking now.”

Williams was born in Washington, D.C., in 1980. His father, Ronald Williams, Sr., was a community developer who was active in local politics until he moved the family to Prince George’s County, just across the District line, in 1985.

“I started crabbing when I was about 5 years old,” says the younger Williams of his waterman origins. “A friend of my mom’s took me to Patuxent Naval Airbase and I had free access to the water and caught a half-bushel of crabs that same day.”

He was 14 when he got his first job on a crab boat. After attending public high school, he studied economics and political science at the University of the District of Columbia and the George Washington University. (Williams has been involved in District politics for years, as a campaign adviser and community organizer. I met him in 2016 as a freelance reporter covering the D.C. government. We talk frequently about local politics.)

Standing nearly 6 feet tall, with a sturdy build, Williams keeps a clean-shaven head, wears a thick beard and has a warm smile. He laughs a hearty laugh, but also has a suffer-no-fools edge.

On his personal website, Burgers Society, he describes himself as provocative, caring and blunt. His worldview is unapologetic: “Don’t care too much about ineffective and excuseful [sic] leaders. Call a spade a spade and throw an ace in your face in a minute.”

Williams had been farming on leased land in 2015 when he was fired from his side job as a forensic psychiatric technician in the maximum security unit at St. Elizabeths Hospital for speaking out against assaults on staff by the patients.

“I made up in my mind that I will never put myself in a position like that again. I decided I was going to start my own business. The next day I started crabbing. It came natural. I caught one bushel in an hour.”

***

Williams is drawn to farming by problems that plague the Black community. D.C.’s Ward 8, on the east side of the Anacostia River, suffers from all the byproducts of poverty and discrimination. More than 72 percent of all adults who are overweight or living with obesity in D.C. live in Ward 8, and Ward 7, which also is located east of the Anacostia, “less than one in every 10 white residents are obese, whereas one in every three African Americans in the District are obese,” according to DC Health.

The prevalence of diabetes in Ward 8 alone is 15.2 percent. That’s the highest in the city, more than 2 percentage points higher than the entire Black population in the U.S., just under two times higher than the national average for whites, and more than six times higher than the average for D.C.’s white population.

Full-service grocery stores are popping up all across the District, but not in wards 7 and 8. Last year, D.C. Hunger Solutions reported that there is just one full-service store in Ward 8 and two in Ward 7.

White crabbers look at you crazy, as if you don’t belong. But they forgot the Native American Indians and Blacks were here first, pioneering agriculture and aquaculture on their behalf.

When he first started farming, Williams approached D.C. government officials about funding to bring healthy, affordable food into the city’s food deserts, and to bring kids who lived in the food deserts into the countryside to work. That went nowhere.

“D.C. was not offering any opportunity and I wasn’t waiting around to beg or grovel for any either,” he tells me, in one of our many email exchanges.

He set his sights on Maryland.

“I leased land to start. I regarded my lease phase as professional development. That process started with me jumping into the training and extension programs that Maryland has to offer,” Williams explains. “From farm start-up to financing, they pretty much had it laid out.”

Williams identified another opportunity in the region. “They got a lot of white farmers that are retiring or getting out of farming, hoping that their kids or their grandkids would someday pick up the business, and to their demise they didn’t… The generations went off to college and never came back, only to set themselves and their families up for the ultimate pendulum to fall,” he says of the legacy farmers of Delmarva. “They’re going out and I’m coming in.”

He was a novice, but as soon as he had saved enough capital from farming and side jobs — like at St. Elizabeths Hospital — he acquired his first piece of property and began networking with stakeholders in the farming community.

“I wanted them to teach me the basics,” he says of a local organization’s Sustainable Agriculture’s Beginning Farmers Training Program. “They pair you with a regional farm. But they put me on a farm that discouraged me. They doubted I would be able to land-farm and water-farm in a season.”

He left the program and enrolled for select courses with the Food and Drug Administration’s Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point Seafood Working Group to learn about food safety assurance, from oyster harvest to consumption, for example.

If there was a professional certification that allowed him to expand as a full-service grower, waterman, food processor and distributor, Williams went after it: produce safety, professional food manager, Maryland Department of Agriculture food safety certification — to name a few.

Today, in addition to direct-to-home and market delivery of fresh produce and seafood, he does wholesale distribution to restaurants in D.C. and Prince George’s County, and, through a contract with USDA, provides “farming to families” boxes in multiple counties in Maryland to eligible recipients of food assistance.

He also provided farm-to-table meals, three times a day for four days, to 1,000 National Guard troops from New York who deployed to secure the presidential inauguration.

Williams shares an industrial kitchen in Gaithersburg, MD, where he processes crab meat and prepares meals from leftover farm produce for delivery through DoorDash, GrubHub and UberEats.

It’s cheaper than getting his own licensed kitchen, he says, and besides, he’s moving his whole base of operations out to the Eastern Shore, where he stays on the lookout for affordable properties.

Recently, Williams acquired 2 acres in Somerset County for $423. He’ll plant soy and corn. He’s got his eye on an adjacent parcel that might have a zoning issue over its current use, which he figures will drive the price down.

Williams’ Smith Island gambit ties directly to his own struggles for independence and autonomy.

In 2017, Williams and his wife, who was pregnant with their daughter, lost the lease on their apartment when their landlord sold it out from under them. Essentially homeless, the setback caused his family and friends to doubt he could make it as an entrepreneur. “It was kerosene, and they didn’t know it,” he says. “It drove me harder to prove them wrong.”

Williams also noticed inequities that rubbed him wrong and gave him an idea: “I [saw] fresh crabs being sold at a seafood market out of a back loading dock to white customers, while Black customers were lined up out the door purchasing cold, cooked crabs at top dollar.”

So, he got certified as a waterman and obtained a commercial fishing license, he says, and took another training course in hazard analysis for shellfish stripping. Now R.T. Williams Seafood, Corp. is a certified shellfish dealer in Maryland.

“I had to stare down challenges,” he says. “Doubt from family, laughs from friends and haters, access to capital because I’m Black… Crabbing on the Eastern Shore is a challenge of its own. White crabbers look at you crazy, as if you don’t belong. But they forgot the Native American Indians and Blacks were here first, pioneering agriculture and aquaculture on their behalf.”

***

The Chesapeake Bay is American’s largest estuary. On the Eastern Shore, 8 percent of Marylanders live and subsist on fishing, blue crabbing, oyster harvesting, large-scale chicken farming and tourism. Aboard the Jason II, as we travel across the bay, I ask Williams why he’s going 154 miles from home to pursue his vision.

He says that when the pandemic began, he wasn’t doing much farming, and with time on his hands he started reading books like Tom Horton’s memoir of living on Smith Island, “An Island Out Of Time”; and “Beautiful Swimmers: Watermen, Crabs and the Chesapeake Bay” by William W. Warner. “I chose Smith Island and Crisfield because it’s the seafood capital of the world and land is cheap,” he says, matter of factly.

His initial step was to book a room at the Smith Island Inn for eight days to get acquainted with the island and its inhabitants. “Just stayed here to get enmeshed with the community, get to know the place, let them see my face — to see if they’ve even seen my face before, heh.” (There’s one other Black couple who live on the island, he says.)

Disembarking, we walk a half-mile or so on cracked asphalt lined not with sidewalks but spongy grasses, brackish puddles, oyster shells and berms. Crab pots are scattered around people’s yards and residents tool around on golf carts. Being Sunday, only the occasional truck passes us by.

Coming to a ramshackle, white wood-frame farmhouse with a Cherokee Red roof and shutters, almost to a marsh that stretches to the bay, Williams begins to consult with his concrete mason, Juan, and his house “mover,” Jerry, an amiable Trump supporter who lives on a nearby island.

The house was on piers for 100 years, Williams explains. Because of sea-level rise, Jerry is going to raise the house 8 feet off the ground with new posts planted either on wood or metal pads. (“The mayflies will only go up to 6 feet, so this way they shouldn’t bother you,” he says.)

After a quick inspection of the interior, Jerry comes out and declares that “she’s got good bones,” though it will have to be completely gutted and re-roofed. “You’ll have to get rid of the fireplace; that chimney’s in the way.”

Williams bought the house for $4,000 and he estimates that a complete renovation will cost him $175,000. When finished, he will be able to take delivery of local crabs, combine them with his own, sort them and then ship them to Crisfield. Most crabbers pick and pasteurize a percentage of their crabs to sell at market as lump meat or crab cakes. Williams has even bigger plans.

Eventually, a bed and breakfast, local restaurant and Airbnb will grace the property, he says, along with a “day post” for visitors to purchase a snack or a reminder of their trip from the gift shop. (The menus will include the famous multi-layered Smith Island Cake.)

“The travelers that come to my spot will then have the opportunity to patronize local business in Smith Island,” he says.

Back in Crisfield, from where this ferry started out, Williams plans to buy an abandoned bank building near the harbor where he’ll also pasteurize and sell crab cakes and lump crab meat; there, he will aggregate, sort and box up the produce he has harvested and purchased wholesale, and ferry it to Smith Island — sparing residents the 80-minute round-trip ferry that costs $20 each way to go grocery shopping.

The building also will feature a cafe for locals and tourists to buy provisions to take on their trip to the island.

More than 400 crabbers used to live on Smith Island, says Williams. Now the total population is less than half of that. The local economy could use a shot in the arm, he says. Expanding the market for their crabs, bringing them fresh farm produce and eggs, and attracting visitors with cash to spend, could be a boon for the community.

***

As Williams is forging his own path, President Joe Biden’s appointment of Tom Vilsack as secretary of agriculture has drawn criticism due to Vilsack’s first stint in the Obama administration.

In January, Vilsack told the Washington Post he had been making calls to Black farmers in various states to hear their concerns of “socially disadvantaged producers.”

“I left the meeting hopeful,” said Cornelius Blanding, head of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives. “There was acknowledgement that there were things he could have done or wished he had done during his eight years.”

Vilsack is being made to own the flawed implementation of the largest civil rights settlements in U.S. history: In 1999, a class-action lawsuit against the USDA known as Pigford v. Gluckman resulted in more than $1 billion settlements with 13,000 Black farmers; in 2011 a federal judge approved another $1.15 billion for Black farmers under Pigford II.

Payments under the first settlement were delayed and insufficient to retire the farmers’ debts, however, and were denied under the second settlement, causing many to lose their farms.

Five U.S. senators have joined New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker in re-introducing the Justice for Black Farmers Act, which proposes to extend land grants to rectify those losses by increasing the amount of Black-owned farmland by 32 million acres over 10 years.

Black farmers should be assertive in claiming that relief, Williams says. “Show them I can take the loan, pay it back, and run a successful business.”

Recently qualified to apply for all federal grants, Williams continues to hunt for land. “Buy cheap and hold,” he says, with a hearty laugh.

Though Williams is crafting an affordable DIY endeavor on his own terms, the underpinnings of discrimination still gnaw at him. “People love talking about equity, but when it comes to doing something, they don’t want to touch that shit,” he says of the co-ops and alliances that promote a “sustainable foodshed” nurtured by education, advocacy and research.

One would think such progressive rhetoric would signal hope for Black farmers like Williams. Not so, he says. “They don’t want to help me get to the roots of what enslaved my ancestors.”

He calls the mantra of the sustainable farming community a “ruse,” a form of patronage of which he wants no part. It doesn’t work for Black farmers, he says. Access to capital and land is what is needed to address history ills visited by Black farmers (see Dean Kuiper’s “A Grievous Harvest” story) and that is still beyond reach for many.

They’re going out and I’m coming in.

“It hasn’t changed,” says Williams. “If you’re Black, if you’re leasing land from other people, if you’re working for other people or doing things for other people because you think you have to, I don’t care how big a deal you think you are. You might as well be a sharecropper. I’ve been on that merry-go-round, but now I’m off it.

“I’m small and nimble. Five-acre lots, a small crew, maybe hire some friends from college when they aren’t working; make a small profit, put it in the bank, create our own future with the financial leverage to bring this multi-layered, multi-use enterprise to Smith Island.”

Eventually, he’d like to set up a similar multidimensional hub in the District, in downtown Anacostia. “I’d tailor that more to the community, create a space that mirrors Smith Island but also offers swimming and boating lessons, charter services, educational classes — make it a meeting point for residents and use the bay and my other facilities as a training ground,” he says.

Williams can’t help but note that 19th-century abolitionist Harriett Tubman once lived in Dorchester County, one county over from Somerset. And that the former home and estate of Frederick Douglass, a National Historic Site, is a short distance from where his family owns property in Ward 8.

These are more than symbols to him.

“If we talk about how black lives matter, we gotta talk about history,” he says. “What does that look like for minorities? How does this diaspora work for all of us? America’s been fucking us around for years. Nibbling and dabbling us, telling us that we have to pull ourselves up by the bootstraps. Well, why not pull ourselves up by America’s original sin, which is agriculture?”

Help us sustain independent journalism...

Our team is working hard every day to bring you compelling, carefully-crafted pieces that shed light on the pressing issues of our time. We rely on caring supporters like you to help us sustain our mission. Your support ensures that we can continue to provide deeply-reported, independent, ad-free journalism without fear, favor or pandering. Support us today and make a lasting investment in the future.