Wrong Place, Wrong Times

UPDATE (as of May 8, 2022):

Judge Tosses Out Rogelio Vasquez Solis Murder Conviction

After spending nearly 30 years in jail for throwing a clod of dirt at a truck, Rogelio Vasquez Solis may soon finally go free. Just weeks after Red Canary Magazine ran our story on the plight of Solis, Orange County Superior Court Judge vacated the second-degree murder convictions against Solis and Saul Penuelas. Penuelas was recently granted parole, leaving Solis as the last remaining member of the so-called San Clemente Six still serving time. Solis was not connected to the cause of the tragic death of 17-year-old Steven Woods during a parking-lot melee at Calafia State Beach. Solis was convicted in 1995 under trumped-up legal standards in an era of highly politicized, anti-immigrant hysteria.

The judge’s decision to vacate the charges was based on a 2019 California law that holds you can’t convict someone of felony murder who didn’t kill anybody or intend to kill anybody. Though 30 years too late, the judge’s decision overturns a miscarriage of justice that our reporter, Nick Schou, never stopped caring about. See story below.

On October 15, 1993, Rogelio Vasquez Solis was riding his bike near his house in San Clemente when a friend in a pickup truck spotted him and asked him if he wanted to go to Taco Bell. It was a Friday afternoon and Solis—as he’s known in court records, thanks to a misunderstanding about Hispanic surnames—said yes, tossing his bike in the back of the truck. At the restaurant, he and his friend bumped into some other kids from the neighborhood who said there was going to be a party at the beach after the local high school football game. In other words, it was shaping up to be a typical Friday night in suburban, coastal Southern California.

Though, it was less typical for Solis, who had just turned 17 years old and hadn’t done much partying. Between hanging out and playing sports at San Clemente High School’s after-school program, delivering papers and helping out at his dad’s landscaping business, he didn’t have much time for the usual teenage diversions. Still, he was a gregarious kid and eager to meet girls. So, Solis rode with his friend to Calafia State Beach, where they met up with some local kids, cracked open a few beers, and waited for more friends to arrive.

There were other teens partying in the parking lot, too—mostly white kids, lower down near the sand. At some point, Solis remembers, someone drove a truck down to the lower lot. Minutes later, vehicles that had been previously parked below were racing up the hill to the upper lot while his friends said something about a fight. Everyone grabbed whatever they could to defend themselves. As one of the vehicles from the lower lot sped by, Solis tossed a clod of dirt and rock at the rear of the vehicle.

The rock bounced harmlessly away, which is why when an Orange County Sheriff investigator questioned Solis a few days later, asking him if he was at the beach and if he threw anything at a car, he readily admitted what he’d done. “They kept asking me who threw the paint roller,” Solis later recalled. “I was like, ‘What paint roller?’”

***

Ironwood State Prison sits in a barren and windswept desert plain just south of Interstate 10 near Blythe, California, about halfway between Los Angeles and Phoenix, Arizona. You can’t see it from the freeway, but there’s a sign on the side of the sand-blown road warning motorists not to pick up hitchhikers. The prison consists of low-slung concrete housing blocks surrounded by tall fences topped with razor wire and guard towers. Aside from a range of treeless rocky hills in the far distance, there’s nothing to see other than cracked earth and the occasional wispy high-altitude cloud.

Five years ago, in 2017, I drove to Ironwood to visit Solis. He was more than an hour late to our meeting in the prison cafeteria. The guards told me he was busy playing baseball out on the recreation field. Solis was still sweating and slightly out of breath from the game when he sat down.

Among the several dozen other inmates in the visiting area, he was the only one without any visible tattoos. He greeted me with a warm smile that rarely left his face during the hour or so I spent with him. As he spoke, he kept smiling and shaking his head in disbelief that I’d made the drive out to see him. Other than a lawyer who was interested in his case, he said that I was the only non-family visitor he’d had since he’s been behind bars.

What landed Solis in prison was, by all accounts, a nightmarish event: the death of Steve Woods, a white teenager, during an encounter with a group of Latino youths that included members of the San Clemente Varrio Chico gang. Although originally labeled an accident by police, the narrative of the chaotic and tragic night turned into one of an orchestrated gang murder once the media and political firebrands got ahold of the story.

The death occurred during an era of sweeping tough-on-crime, anti-gang measures, as well as anti-immigrant foment, that led up to the state legislature passing Proposition 187 under Governor Pete Wilson. In that heated climate, law enforcement officials and media outlets spread fears that Woods’ death represented the opening salvo in an anticipated wave of deadly gang violence by illegal immigrants from Mexico.

In time, the case would become part of the wave of anti-Mexican immigration hysteria that swept California in the 1990s—the founding mythology of the superheated, xenophobic politics of the Trump era.

Although the events that put Solis in jail occurred decades ago, it merits revisiting in the current context, during which it’s possible that 17-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse, a white teen who fatally shot two unarmed people with the assault rifle he carried across state lines and flaunted in the middle of a protest, was found to be acting in self-defense.

Compared to the leniency afforded to Rittenhouse, the Solis case raises difficult questions about race and immigration status when it comes to America’s justice system. Despite having no prior criminal record, 17-year-old Solis was tried as an adult and sentenced to 15 years to life in prison for throwing a clod of dirt.

Repeatedly denied parole, he’s now been behind bars for almost 30 years.

***

Solis grew up in San Clemente, a beach town in south Orange County, but he was born in a rural area of Guanajuato, Mexico. He is the son of parents who headed north for work. Although both his parents were born in Mexico, his grandfather had moved to San Clemente decades earlier and obtained U.S. citizenship. Solis’s father operated a small landscaping business and for work, Solis helped his dad mow lawns and trim bushes when he wasn’t delivering papers. When he was arrested, he and the rest of his family were all in the process of seeking citizenship.

The neighborhood where Solis lived was inhabited by a small street gang that went by San Clemente Varrio Chico, or SCVC, that occasionally beefed with a larger, older gang based in San Juan Capistrano, the Varrio Viejo. While Solis was growing up, both of his older brothers had been members of SCVC. The oldest one ended up in prison for allegedly participating in the murder of a Varrio Viejo member. The middle brother spent a few months in juvenile hall before he gave up the life, got straight, worked his way up the ranks at a local landscaping company and eventually raised a family.

Solis never joined SCVC. He preferred to play sports. Unlike other neighborhood kids his age, he didn’t have a girlfriend and didn’t use drugs or drink. He’d only just tried a few sips of beer by the time he was 17. A middling student who struggled with English, Solis was a jovial presence and a well-behaved kid at San Clemente High School, according to school officials. Just days before he was arrested, he’d defused a potential fight between a group of Latino and White teens at a beach by walking up to a white student he knew, patting him on the arm and saying hi.

According to court records, the incident that took place on the evening of Oct. 15, 1993, began when a mixed-race student—who had recently been kicked out of San Clemente High School and was attending a day school for troubled youths—spotted what he thought was a friend’s car in the upper lot where a group of Latino youths, including Solis, had gathered. The young man pulled up and asked if anyone knew anything about a rumored party in nearby San Juan Capistrano. One of the kids in the upper lot didn’t like the mention of the rival town. “Fuck San Juan,” he allegedly responded, according to police reports and newspaper accounts. “We’re San Clemente.”

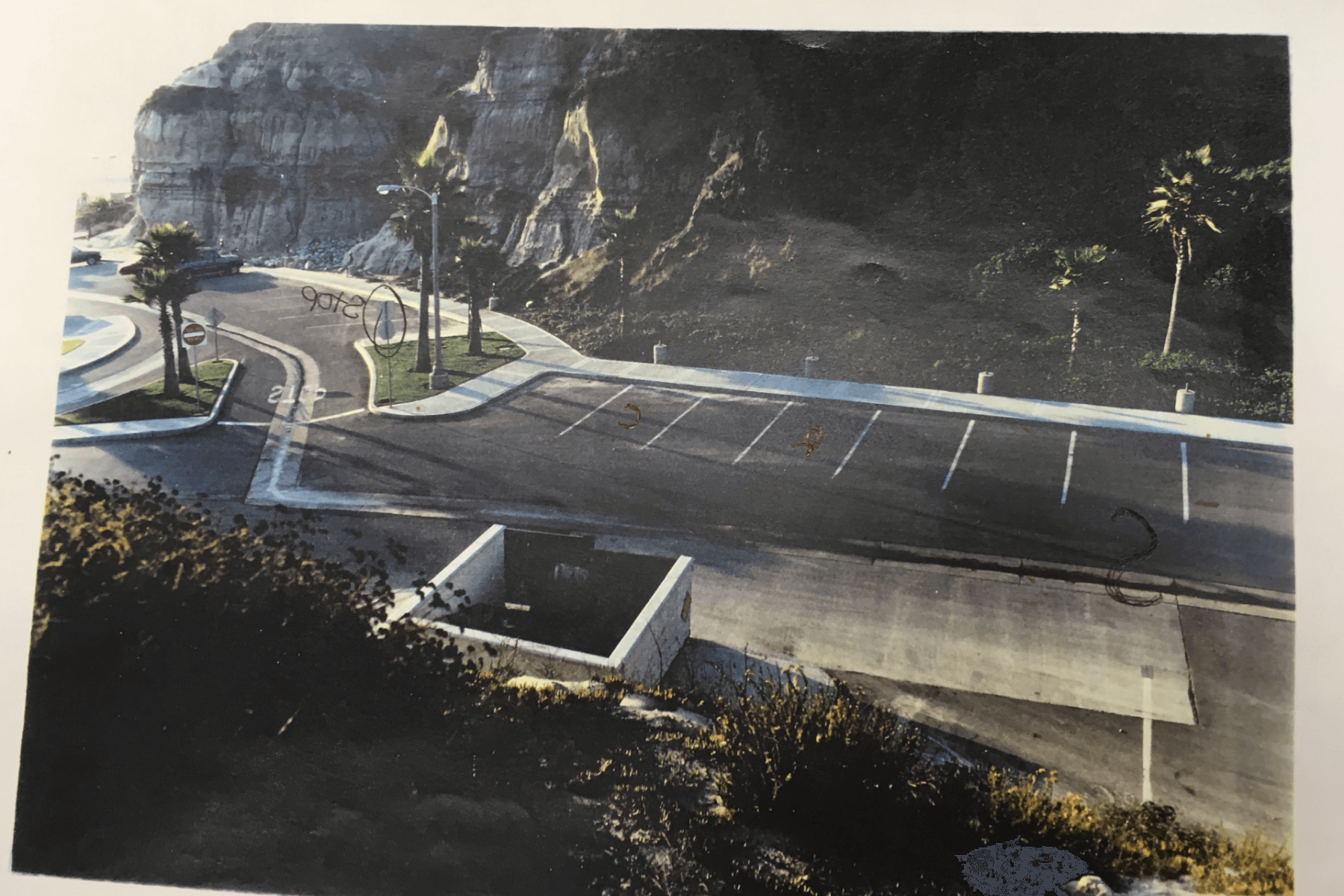

The upper and lower lots along the coast at Calafia State Beach. Photo courtesy of Nick Schou

Then, according to police reports, it occurred to him that the student asking about the party was the same kid who had flipped off him and a friend a day earlier. Still angry about that perceived insult, the kid from the upper lot allegedly punched the young man in the face. The student who had been punched drove down to the lower lot to warn his friends.

Down in the lower lot, the white students piled into their cars. As the kids from the lower lot raced up the hill at up to 35 mph, the Latino youths in the upper lot later told police they readied for a rumble, grabbing whatever objects were nearby—rocks, wood, chunks of concrete, a tennis racquet—to defend themselves. Among the items was a pair of paint rollers that happened to be in the back of a vehicle belonging to the paint contractor father of brothers Hector and Saul Penuelas, who would later be co-defendants.

A total of four vehicles approached the upper lot. The first, a Chevy Suburban, was moving quickly and suddenly swerved to the right, in the direction of most of the Latino youths. The driver later told police that he swerved to avoid one of the teenagers who was holding a tennis racket and standing in the middle of the lot. Interpreting the swerving vehicle as a threat, the Latino kids hurled everything in their hands at the vehicle.

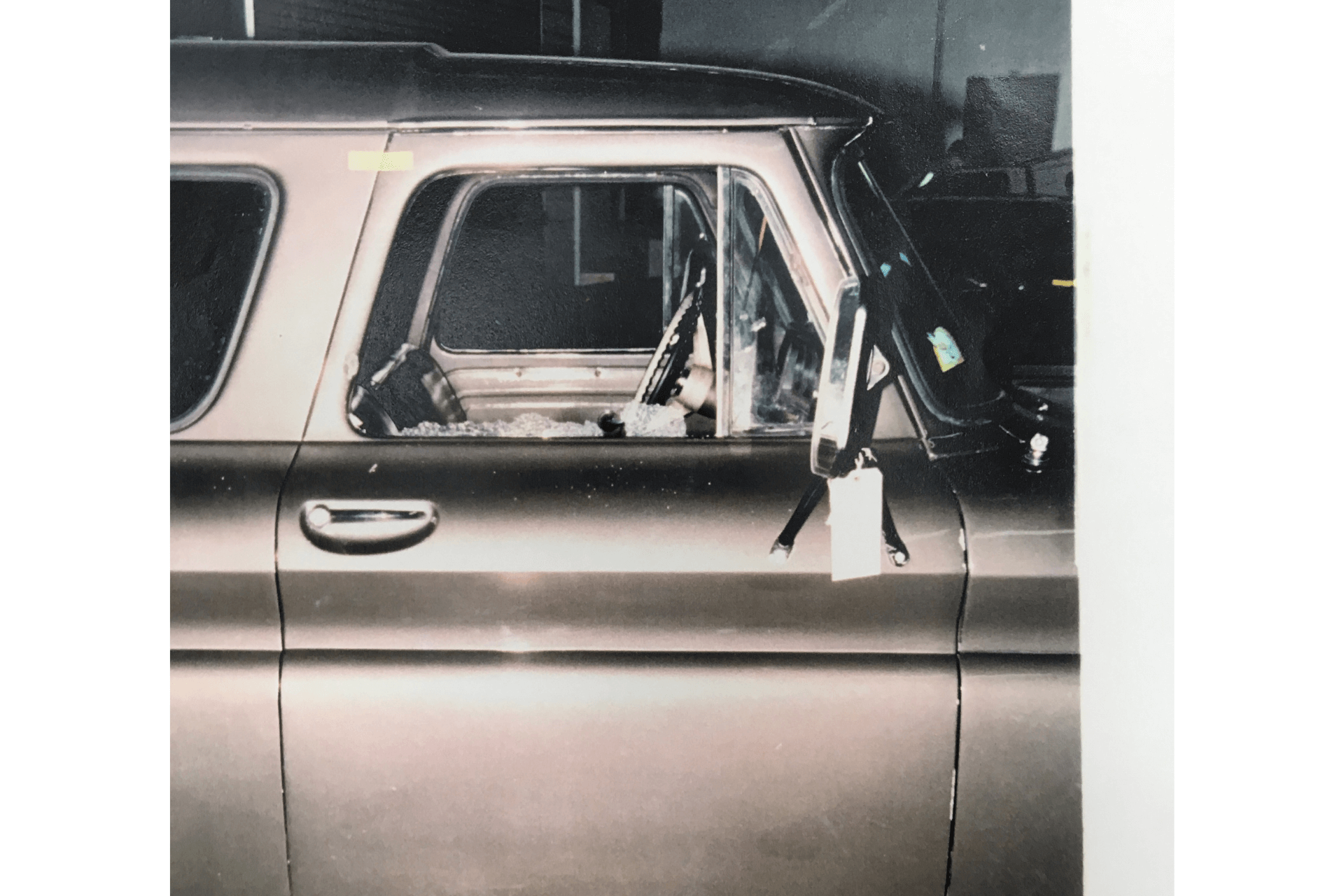

Numerous objects both crashed into and bounced off the exterior of the Suburban, including a block of wood that left a gaping hole in a rear window on the left side of the vehicle. Something heavy also shattered the tinted glass of the front passenger window. Fewer objects hit the second vehicle, which suffered a cracked windshield, a dented fender and a dented door in addition to having beer splattered over it. The third car, which was moving considerably slower, escaped unscathed, except for a splattering of beer. Police records make no mention of any damage to the fourth vehicle.

The shattered window of the front passenger window of the Suburban. Courtesy of Nick Schou

It wasn’t until the convoy was nearly out of the upper parking lot that the Suburban’s driver and a female passenger in the back seat realized that Steve Woods, a 17-year-old student sitting in the front passenger seat, had been seriously injured and was leaning head down, unresponsive. Somehow, one of the paint rollers that had been hurled at the vehicle shattered the right front passenger window and its shaft speared Woods through the side of his skull just above his right ear, penetrating several inches into his brain.

***

Within a couple of days, police had arrested a total of nine people—six of whom were ultimately charged with the attack, including a 21-year-old who confessed to police that he had tossed a paint roller at one of the cars, although he didn’t know if it was the one that had struck Woods in the head. Although doctors at Mission Hospital Regional Medical Center were able to remove the shaft, Woods remained in a medically induced coma and never regained consciousness, dying of his injury three weeks later.

Three days after the incident, the San Clemente Post published a story in which law enforcement officials characterized the incident as a “fluke” and a “one-in-a-million chance.” The Post reported that Sgt. Russ Moore of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department said, “From all appearances, it was a case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

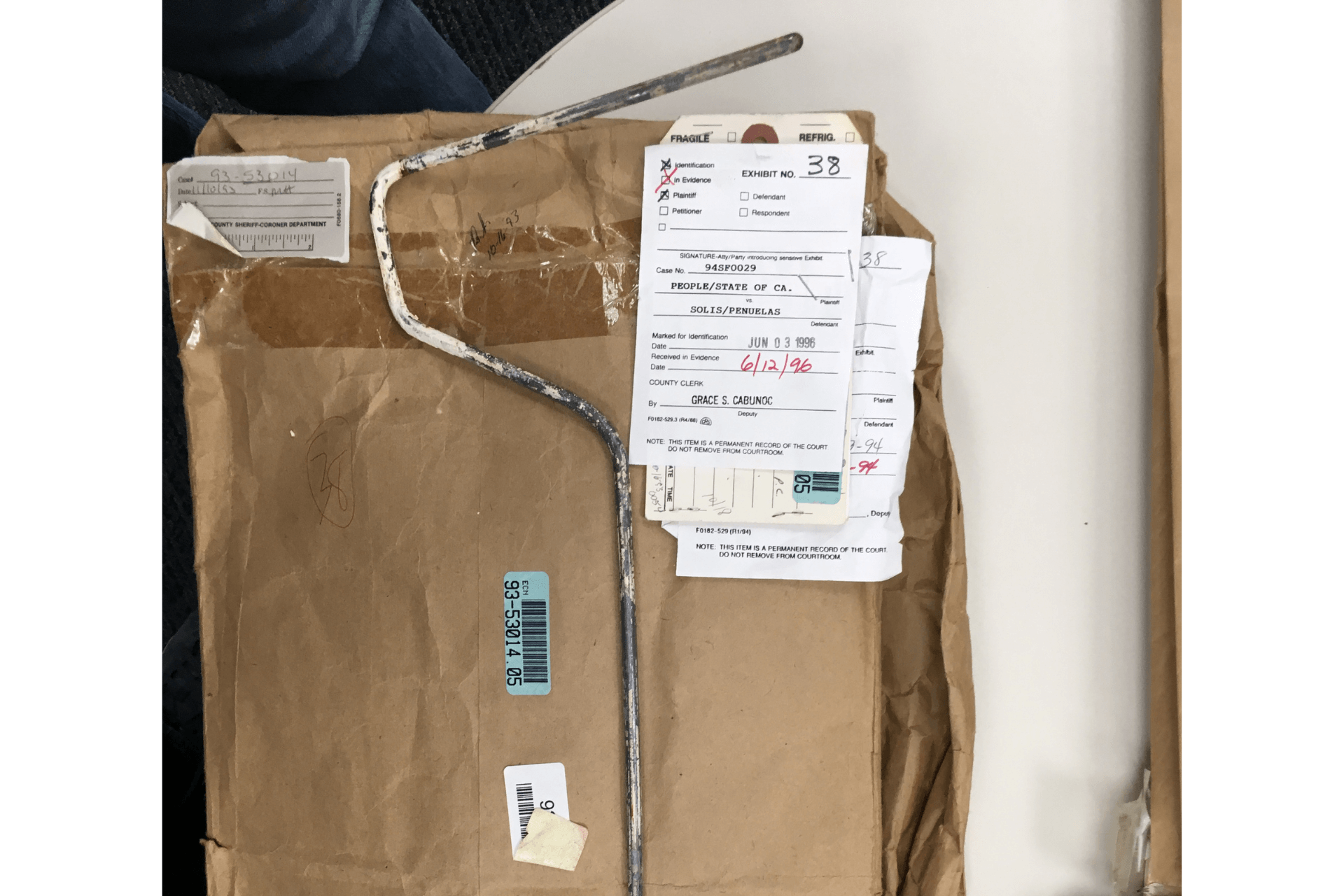

The lethal paint roller booked into evidence. Photo courtesy of Nick Schou

Quickly, though, racial profiling marred hopes for a fair trial. Collectively known as the “San Clemente Six,” each defendant was treated as equally culpable under the gang-enhancement theory of prosecution, in which prosecutors argue that the crime was committed for the benefit and furtherance of the gang.

Many of the Latino youths in the area were known to wear the standard cholo outfit of baggy pants and white T-shirts, which also happened to be the standard uniform of most young, working-class, Mexican-American males in Southern California in the early 1990s. Thus, the teens were readily depicted as either gang members or at least “affiliates” of the gang.

For Solis, the only evidence of any gang ties was the fact that Sheriff’s deputies once interviewed him outside a local skating rink while he was with one of his older brothers. This automatically placed him on law enforcement’s gang monitoring radar, which in those days served as a means of standard profiling and enhancing sentencing for even minor infractions.

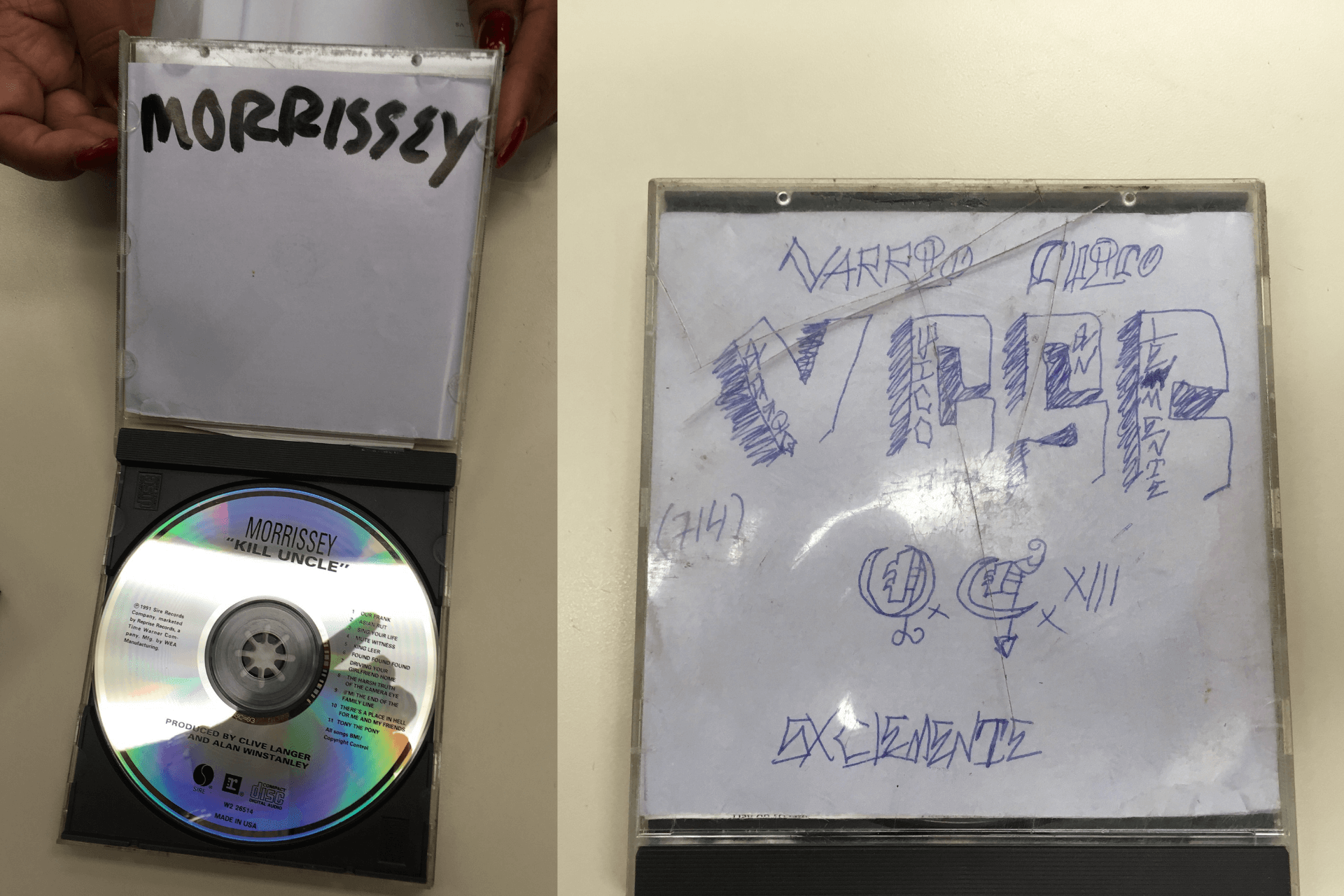

Morrissey is a popular musician amongst Mexican-American youth. This CD was used as evidence in the prosecution. Courtesy of Nick Schou

The prosecution’s gang theory of the case hinged on the notion that when one of the Latino kids allegedly exclaimed, “Fuck San Juan. We’re San Clemente,” he was issuing a threat on behalf of the SCVC gang. The police also cited a Morrissey CD found in one of the vehicles at the scene that had the initials “SCVC” written on it as evidence that all those present were gang members.

The Los Angeles Times led the near-prosecutorial press coverage, reporting that Woods had been “speared” in the head with the paint roller while failing to make clear that it had been tossed at the tinted window of a vehicle driving by at roughly 35 miles per hour. Another story a few weeks later stated that the paint roller had been “thrust” into Woods’ head. On Oct. 19, 1993, the Times published a story titled, “Stabbing Incident Departs From Pattern” reporting that, “experts say the attack by alleged gang members on a group of San Clemente High students signals a new type of assault that doesn’t involve a rival gang.”

A month later, another Times article about a community meeting held in the wake of the tragedy ran under the headline, “In San Clemente, 200 Talk of Halting Spread of ‘Fungus,’” referring to a law enforcement official’s term for gang violence. The article says that Woods was “speared in the head with a metal rod from a paint roller” and quotes police who said that the defendants “are all either gang members or gang affiliates” and that “this is the first time [that] local officials can remember that suspected gang members have seriously attacked a group with no gang ties.”

The Times coverage helped paint a widely accepted picture of an intentionally murderous act of spearing or stabbing a victim, as opposed to the hurling of a random object at a moving vehicle. Coverage also didn’t mention that while some of the defendants were admitted members of SCVC, at least one of them—Solis—did not claim such status, nor did he fit the profile of a gang member. He didn’t shave his head or wear cholo-type attire like the other defendants. Also, neither Solis nor any of the other San Clemente Six—two of whom belonged to a Christian youth ministry—had any prior criminal record, though this was not mentioned.

***

The first two youths to be prosecuted were tried in juvenile court. In keeping with California Law, Orange County Superior Court Judge Everett W. Dickey sentenced them in January 1995 to remain in custody until they turned 25. According to the Orange County Register, Dickey fashioned the sentences with an emphasis on rehabilitation, refusing to sentence them to state prison where they wouldn’t have been eligible for parole until the age of 33.

“Citing psychological evaluations of both youths, [Dickey] said they suffer from feelings of inferiority and inadequacy that they regrettably satisfied through their gang,” the Register reported on Jan. 14. “There’s no justification for what happened,” Dickey said. “Nonetheless, these are not predators in the sense that…they were setting out to kill somebody.”

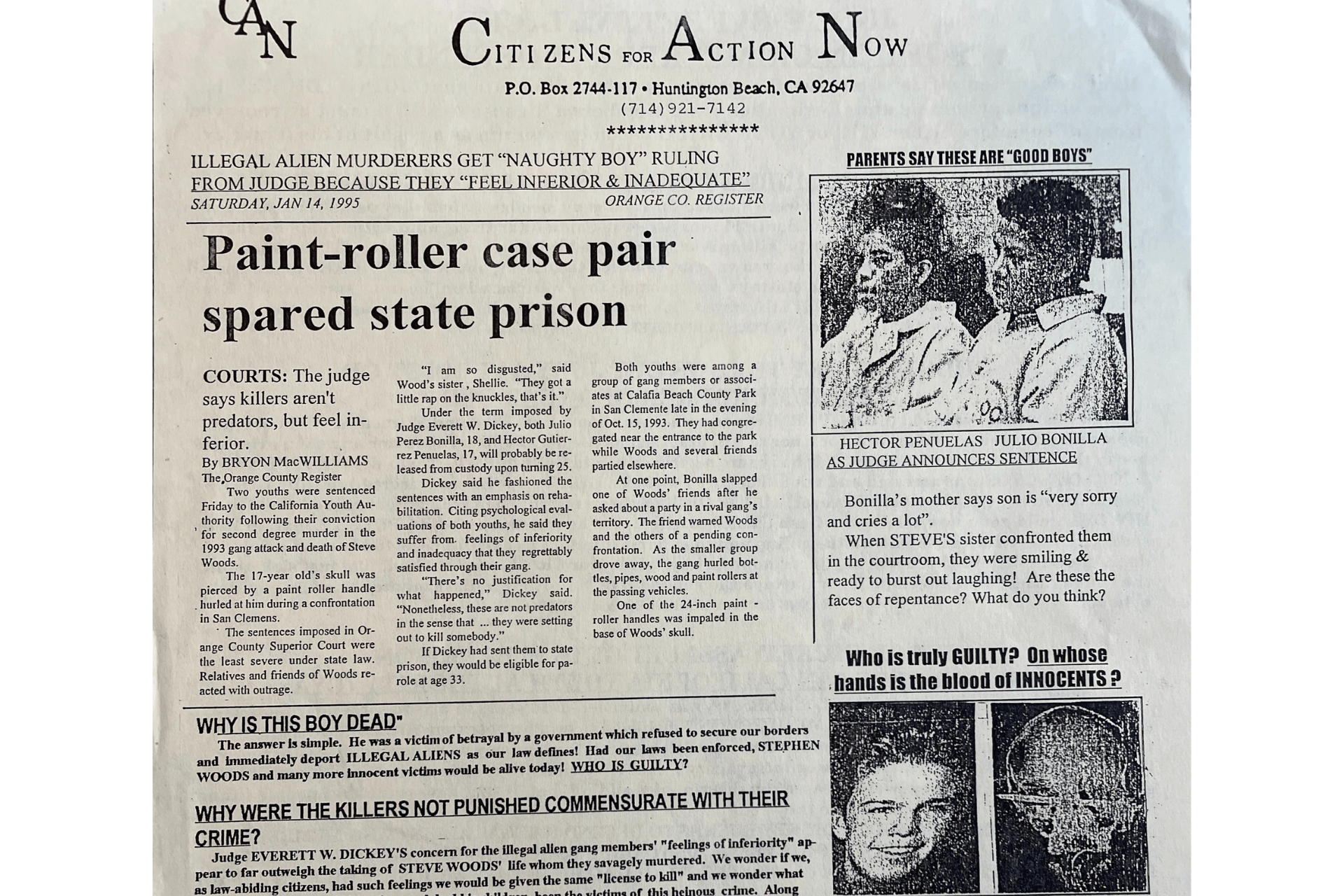

Dickey’s leniency didn’t sit well in conservative Orange County, which was then still in the throes of hysteria over illegal immigration from Mexico. A copy of the Register story about the sentencing of the first two San Clemente Six defendants appeared on a flyer distributed by a Huntington Beach anti-immigration group called Citizens for Action Now (CAN). The flyer featured photos of the two defendants, as well as a photo of Woods taken before the incident and a graphic X-ray image taken at the hospital showing the paint-roller rod in his skull.

This CAN flyer using Woods’ death and x-ray photo was a prototype for the type of populist hysteria that led to voters passing Prop. 187. Courtesy of Nick Schou

“Why Is This Boy Dead?” CAN’s flyer asked. “The answer is simple. He was a victim of betrayal by a government which refused to secure our borders and immediately deport illegal aliens as our law defines! Had our laws been enforced, Stephen Woods and many more innocent victims would be alive today!” CAN further urged the public to support a recall effort against Judge Dickey. “Will your child be next? Will you help recall this judge and send a message to all who make a mockery of our system??”

Woods’s death was used to promote the recall effort against the judge and to rally support for what became the first statewide initiative in the nation to specifically target the children of illegal immigrants. Proposition 187, as it was called on the November 1994 election ballot in California, sought to deny public education to the children of illegal immigrants. In many ways, it was a prototype for the grassroots, anti-immigration, politicking that Donald Trump rode into office.

The law was the brainchild of the California Coalition for Immigration Reform (CCIR)’s notorious, chain-smoking, and since-deceased anti-immigrant activist Barbara Coe. Birthed in the fire of San Clemente Six hysteria, the group’s stated mission was to reclaim California from “illegal aliens” crossing the border from Mexico and “bringing their values and culture to our midst,” causing both “mounting financial burdens as well as moral and social decay.”

Coe and other Orange County activists routinely distributed literature referring to Prop. 187 as the “Steve Woods Memorial Initiative.” Hoping to milk anti-Latino sentiment spurred by the San Clemente Six trial, they distributed campaign pamphlets full of hyperbolic screeds about the spread of Latino gangs and the rise of radical Chicano student activists in California universities.

“This isn’t ‘immigration.’ This is an invasion. And you’re paying for it,” stated one typical CCIR flier. “Close to a million illegal aliens stream across America’s borders every year in violation of our law. Once here, these lawbreakers are ‘rewarded’ with billions of your tax dollars for their health care, education and welfare benefits…These major contributors to our welfare, education, crime, disease and unemployment problems now plan to vote so they can control our government.”

Although passed by state voters in the November 1994 election, Prop. 187 languished in the courts for several years before being ruled unconstitutional under state law. Judge Dickey survived the recall attempt against him, but to the delight of his critics, none of the remaining four San Clemente Six defendants received any of the leniency he offered the first two prosecuted.

Two of the young men quickly reached plea deals and went to prison. After a brief trial on June 19, 1996, the final pair of defendants, Saul Penuelas and Solis, were both convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to 15 years to life in prison.

As Penuelas and Solis left the courtroom in handcuffs following their conviction, a heated exchange with members of the Woods family took place. According to the Orange County Register, during the hearing “the Woods family scoffed repeatedly at those who sought to cast Solis and Penuelas in a positive light, muttering under their breath their belief that the two were gang members.” Amid reported slurs and invective directed at them, both Solis and Penuelas were seen smiling and uttering profanities as they were led away. This incident would later be used by prosecutors as evidence that Penuelas and Solis had no remorse and thus were undeserving of early release.

Eventually, five of San Clemente Six—including Penuelas—either served their entire sentences or qualified for parole. Only Solis remains behind bars today.

***

Mike Males, now a senior researcher at the Center for Juvenile Justice in San Francisco, was a graduate student at UC Irvine during the 1990s. Author of the 1996 book The Scapegoat Generation: America’s War on Adolescents, Males still remembers the immigrant-crime hysteria that spiked with the San Clemente Six trial.

“Orange County was in a state of panic back then,” Males recalls. “There was this fear of an invasion of gangs and the fact the population that was becoming more Latino. Orange County was still a conservative county and prosecutors were on the hunt for a case to show how tough they were on gangs.”

Males specializes in researching crime statistics to punch holes in the myths over immigration and crime that were infecting public debate both in California and nationwide. “Gangs were not a big problem in South Orange County and they were trying to make it look like they were,” he said of the trial and anti-immigration action it catalyzed.

Alone among national media outlets, The Nation magazine cited both the Orange County Register and the Los Angeles Times for slanted coverage of the San Clemente Six trial. In an October 31, 1994 article, noted California social historian Mike Davis lambasted the former for “spread[ing] the fiction that ‘a gang member [deliberately] rammed a metal rod through Woods’ head” and the latter for “transform[ing] Woods into a ‘symbol of tragic proportions’ for Orange County residents fearing a sudden deluge of ‘violent, urban-style crime’ in their ‘quiet coastal haven.'”

In fact, Males observed that most of the violence being committed in Orange County was by white adults. “There were horrific incidents of white perpetrators driving cars into schools or shooting their entire family,” he says. “These cases were prosecuted, but there was none of this media panic around it.”

Meanwhile, despite the perceived threat of Mexican immigration and youth gang violence in places like Orange County, the feared crime wave never actually materialized. Some may argue that this is because California locked up so many people, and about 10,000 youth were indeed incarcerated at state-run facilities during the mid-1990s, according to official statistics. That number had dropped to about 750 youths by 2020—88 percent of which were Black and Latino. Orange County has seen a similarly staggering drop in youth crime and incarceration since the mid-90s nationwide peak in crime.

“When you fast forward to the Trump era, there has been an 80 percent drop in crime in Orange County alone,” notes Males. “It’s fallen through the floor. Right now, there are maybe 50 kids in custody in a county of four million people, so whatever grounds there might have been in early ’90s for panic over gangs, which was wildly exaggerated even then, doesn’t exist today.”

In 2020, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed State Bill 23, which requires the state’s youth prisons to shut down by 2023. Nonetheless, Males says that the media-fueled hysteria over crime remains alive and well, and continues to spread nationwide. “The panic is still there,” he says. “It’s really a ripe situation for someone like Trump to come along and exploit the issues we saw in Orange County 25 years ago.”

It’s particularly disturbing, Males argues, that defendants like Solis remain behind bars decades after committing their juvenile crimes while Kyle Rittenhouse is found innocent of murder despite shooting three people with an assault rifle and killing two of them—all under the watchful eye of police, who did nothing to disarm him when he crossed state lines to provide “security” for local businesses at a Black Lives Matter protest in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

“If Rogelio had taken an assault rifle to this beach in San Clemente and started shooting people, there is no question what would have happened to him if he tried to claim self-defense as Rittenhouse did,” says Males. “Rogelio’s only act of aggression was to throw a clod of dirt when cars were racing around. Rogelio didn’t have an assault rifle; he had a clod of dirt. And he didn’t go to San Clemente to police the beach as an armed vigilante like Rittenhouse, he just went to the beach with people who turned out to have bad associations.”

***

In late 2014, a few years before I visited Solis at Ironwood State Prison, there seemed to be a chance he could finally be released from prison. California is notorious for refusing to grant parole to people convicted of murder, however, Solis had a reason for hope. Taking into consideration the large number of juvenile defendants in California that had been sentenced to life in prison, the law allowed inmates to request special hearings to consider their age and maturity at the time they were charged.

Although Solis had no prior criminal record and had played a small part in the events that led to Woods death, he still had a few obstacles to overcome. Not long after being placed in Orange County Jail while awaiting trial for the Woods murder, he’d been present during at least one gang-related fight in the jail. A more recent prison behavior citation relating to possession of an illegal cell phone was also staining his record.

Shirley Juarez, an attorney who defended Solis in his murder trial, wrote a letter to the California Parole Board noting her client’s minor role in the incident, as well as the fact that a San Clemente High School teacher had testified at his trial that he wasn’t a gang member. “At the time the prosecutor told me himself, this was just a terrible accident,” Juarez wrote. “But after the media took off with this, I could not get any offer from the prosecutor…I believe the prosecution by that time needed to look very tough because someone had died.”

During the hearing, a Woods family member told the board over the telephone that, thanks to the murder, she still feared for her safety even though she no longer lived in California. “I believe I will never be able to be who I was supposed to be because of seeing too much, too young,” she said. “I’m still scared, and I don’t even live in the state anymore.”

The Parole Board denied Solis his request for leniency. Kathy Woods has continued her fight against illegal immigration, which she sees as the root cause of her family’s tragedy. On Aug. 31, 2016, when Trump gave his infamous “build the wall” speech in Phoenix, he brought onstage more than a dozen family members of people murdered by illegal immigrants for his traveling “A Stolen Life” show. “All I can say is if Mr. Trump had been in office [back] then,” Woods told the crowd, “our border would have been secure, and our children would be alive today.”

Not long after I visited Solis in prison, I met with his family at a Mexican restaurant in San Clemente. (The family asked that I not use their first names). His family affirmed the events leading up to Solis going to the beach on that horrible night.

Solis’ older brother affirmed, too, that unlike some of the kids in the neighborhood—including himself—Solis had no interest in gangs. “He would always be in school or playing sports at the Boys and Girls club,” he told me. “He never dressed as a gang member. He never shaved his head and always had long hair. He had two paper routes he’d always do after his homework. Every Christmas, he’d get really good tips.”

The brother said that Solis had just started showing an interest in girls, which is why he believes Solis agreed to go to Calafia State Beach. “He heard there were girls, and so he went,” the brother said.

“That’s how he ended up at the beach,” Solis’ mother agreed, wiping away tears. “He would never go out. He goes out one time and this is what happened. He was a good boy. He had absolutely nothing to do with gangs. When I found out Steven Woods had died, I was shocked. But, my son didn’t even know him. He only threw a chunk of dirt at the car. I don’t understand why he has to be locked up for 25 years.”

***

In the months and years after my visit with him at Ironwood (more recent requests to visit with Solis have been denied due to Covid-19 restrictions), Solis wrote me a series of letters detailing the events that led up to his arrival at Calafia State Beach. The letters said pretty much the same as his family: he was riding his bike when a friend offered to take him to Taco Bell and that he agreed to go to the party on the beach, hoping to meet girls.

He also recalled the racism he says he experienced growing up in San Clemente, including occasionally being called a “beaner,” and how he feels that impacted the fight that broke out at the beach. “Inside school [and] outside school, people were getting tired of this,” Solis said. “There were always fights between blacks and Mexicans. I was trying to stay out of trouble because I was getting ready to go to college.”

He talked about how difficult it was to survive in prison, and how he played sports to avoid depression and stay out of trouble. He said he still hoped to go to college someday. Solis admitted that, while in prison, he’d adopted a tough nickname, “Shanker,” which he used to sign off on letters to people outside. He claims the nickname is a joke. “Every day is survival in here. The only thing I want before I die is to go back to the beach where I grew up,” he said.

In 2018, then-Governor Jerry Brown denied Solis’s petition for clemency, which was strongly opposed by the Orange County District Attorney. He has since been transferred from Ironwood State Prison to North Kern State Prison in Delano, California. Arguing that the material didn’t include “information relating to the conduct of the public’s business,” the California Department of Corrections denied a public-record act request for documents, including disciplinary records, which might be relevant to Solis’s chances for parole.

In his letters to me, Solis also expressed sympathy for the pain the Woods family have experienced, but also said he couldn’t understand their desire to keep him behind bars—a desire, he says, is apparent every time he goes before the prison board. “I get shut down because they say that I am still a threat to society,” says Solis.

His next hearing on parole eligibility is scheduled for June 1.

Help us sustain independent journalism...

Our team is working hard every day to bring you compelling, carefully-crafted pieces that shed light on the pressing issues of our time. We rely on caring supporters like you to help us sustain our mission. Your support ensures that we can continue to provide deeply-reported, independent, ad-free journalism without fear, favor or pandering. Support us today and make a lasting investment in the future.

Looks like he is getting out!?

Very sfsdfsd

I’m very sorry this happened. Just seeing the name of the gang, I feel bad, since I’m the one that started the gang and gave the gang its name, sorry once again.